- A. FOREWORD

- B. WELCOMING ADDRESSES

- C. OPENING SESSION: OVERVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY

COMMITTEES OF INQUIRY (PCIS) IN ECPRD MEMBER PARLIAMENTS

- D. SESSION 1 - PARLIAMENTARY

COMMITTEES OF INQUIRY AS A TOOL OF SCRUTINY OF THE EXECUTIVE

- 1. Parliamentary inquiries in Ireland: an overview

of legal and structural challenges, Mrs Cathy EGAN (Houses of the

Oireachtas - Ireland)

- 2. Bicameral inquiry committees in the Italian

experience,

Mr Luigi GIANNITI (Senato della Repubblica - Italy)

- 3. Parliamentary committees of inquiry and the

“drawing right” in the French Senate, Mr Jean-Pascal PICY,

Senior advisor at the Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee

(Sénat - France)

- 4. Question-and-Answer session

- 1. Parliamentary inquiries in Ireland: an overview

of legal and structural challenges, Mrs Cathy EGAN (Houses of the

Oireachtas - Ireland)

- E. SESSION 2 - INVESTIGATIVE POWERS,

METHODS AND TECHNIQUES

- 1. The resources available to parliamentary

committees of inquiry and the methodology for gathering evidence, Mr Frank

RAUE (Bundestag - Germany)

- 2. Legal and practical limits to investigative

powers, Mrs Rita NOBRE (Assembleia da

Republica - Portugal)

- 3. Parliamentary inquiries in practice in the Dutch

House of Representatives, Mr Rob DE BAKKER and Mr Martijn

VAN HAEFTEN (Tweede Kamer - The Netherlands)

- 4. Question-and-Answer session

- 1. The resources available to parliamentary

committees of inquiry and the methodology for gathering evidence, Mr Frank

RAUE (Bundestag - Germany)

- F. SESSION 3 - COLLABORATION AND

CONFLICTS WITH OTHER INSTITUTIONS, INCLUDING THE JUDICIARY

- 1. The consultation procedure in the Austrian

National Council - A mechanism to ensure due consideration to the

activities of prosecuting authorities, Mr Alexander FIEBER

(Nationalrat - Austria)

- 2. The role of investigation committees in

prosecuting Cabinet members, Mrs Konstantina - Styliani GAVATHA

(Voulí ton Ellínon - Greece)

- 3. Parliamentary privilege of witnesses, Mrs

Rhiannon WILLIAMS (House of Lords - United-Kingdom)

- 4. Question-and-Answer session

- 1. The consultation procedure in the Austrian

National Council - A mechanism to ensure due consideration to the

activities of prosecuting authorities, Mr Alexander FIEBER

(Nationalrat - Austria)

- G. CONCLUSIONS

- H. OVERVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES OF

INQUIRY

A. FOREWORD

Founded in 1977, the European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation (ECPRD)1(*) brings together 63 parliamentary assemblies from 50 States, as well as the European Parliament and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

The French Senate takes an active part in its work through the Comparative Law Unit of the Department for Parliamentary Initiative and Delegations, two officials of which act as the Senate's correspondents to the ECPRD.

The organisation of the ECPRD is structured around five areas: “Parliamentary Practice and Procedure,” “Parliamentary Libraries, Research and Archives,” “Information and Communication Technologies in Parliaments,” “Economic and Budgetary Affairs,” and “Exchanges related to the General Data Protection Regulation.”

Each autumn, the ECPRD brings together all the correspondents of its member assemblies. In addition, the areas regularly organise thematic seminars gathering specialists identified within parliamentary services.

The topic of parliamentary committees of inquiry has, for several years, attracted sustained institutional interest. In this context, and under the aegis of the “Parliamentary Practice and Procedure” area, the French Senate hosted on 12 and 13 June 2025 a seminar devoted to this subject.

This document contains the proceedings of that seminar.

B. WELCOMING ADDRESSES

1. Mrs Sylvie VERMEILLET, Vice-president of the Senate responsible for parliamentary work and the conditions for exercising the mandate of senator

Mr Secretary General of the Senate,

Ladies and gentlemen,

Dear members of the European Centre for Parliamentary Research and Documentation (ECPRD),

In my capacity as Vice-President of the Senate and Chair of the Bureau delegation responsible for parliamentary work and the conditions under which senators carry out their duties, I would like to welcome you to the French Senate. Today, nearly 60 civil servants and employees from 30 parliaments in 29 countries, as well as from the European Parliament, have come to participate in this thematic seminar on parliamentary committees of inquiry.

I am delighted in many ways to host this event within our institution:

- firstly, it is fully in line with the Senate's efforts to promote interparliamentary cooperation. Although not yet widely known, the ECPRD network makes a vital contribution to cooperation between different parliaments in the areas of research and documentation. It enables us to exchange information more effectively, as well as ideas and experiences on topics of common interest. One example is the essential role played by the network in facilitating the rapid exchange of information on the measures implemented by parliaments during the COVID-19 pandemic or, more recently, the sharing of information on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in parliamentary assemblies.

The Senate had not hosted a ECPRD event since the 2016 annual conference, which was co-organised with the National Assembly. With this seminar, we are confirming our full involvement in this network, which I am delighted about;

- secondly, this seminar demonstrates our institution's interest in comparative law. Since 1995, the Senate has had a Comparative Law Unit, which is part of an ad hoc directorate, and that also acts as a `correspondent' for the ECPRD. This division produces numerous comparative law studies, particularly in the context of parliamentary oversight and at the request of committees of inquiry. Once adopted, these studies are all made public and widely available on the Senate's institutional website. Having this in-house expertise is invaluable in informing our work. Sometimes, legal solutions developed abroad can also be a source of inspiration for future reform proposals or even legislative initiatives.

- thirdly, the theme of this seminar - committees of inquiry - is of particular importance to the Senate. Our Upper House plays an essential role as a counterweight to the executive, and the exercise of this supervisory function often takes place through committees of inquiry. Since the inclusion of committees of inquiry in the Constitution in 2008, followed by the enshrinement in the Senate's rules of procedure of the annual “drawing right”(droit de tirage) of political groups, the Senate has set up more than 40 committees of inquiry, a historically high figure and probably unmatched in most of your parliaments. This is without counting the cases where the prerogatives of committees of inquiry have been granted to standing committees. At this very moment, five committees of inquiry are in session in the Senate and will very soon complete their work.

Committees of inquiry thus occupy a significant part of the activity of senators and the administration that supports us in our work.

For my part, without prejudice to my various responsibilities within the Bureau, my parliamentary group, the Finance Committee and the Delegation for strategic foresight, I am currently a member of the Bureau of the Committee of Inquiry into Financial Crime, created on the initiative of the Union Centriste group, to which I belong. The aim of this committee of inquiry is to elaborate further on the Senate's existing work on this subject. We felt this was necessary in view of the hold that organised crime has in France today and the scale of the financial resources linked to criminal activities.

In 2020, I was also co-rapporteur for the committee of inquiry into the government's handling of the Covid-19 health crisis. This committee of inquiry was set up at the request of the President of the Senate, Mr Gérard Larcher. Within a few months and under the difficult health conditions we all remember, we conducted 47 hearings, heard from more than 130 people, requested hundreds of documents and consulted numerous archives. This work resulted in the adoption in December 2020 of a 500-page report that meticulously analyses France's state of preparedness on the eve of the outbreak and the management of the health crisis by political and administrative leaders.

Our conclusions were clear: like many European countries, France was not prepared for such a pandemic. However, the sad episode of the mask shortage will remain a symbol of the serious consequences of a lack of preparation in the initial fight against the virus, which fuelled the confusion and even anger of healthcare workers and many of our fellow citizens. On this point in particular, the work of the committee of inquiry showed that the disappearance of the strategic stockpile of protective masks in the 2010s was the result of a deliberate decision by the administration not to replenish this stockpile. Furthermore, this shortage was deliberately concealed at the start of the epidemic.

Based on a body of evidence and well-supported arguments, our committee of inquiry was thus able to provide reliable information to our fellow citizens and had a significant impact on public opinion, as its conclusions, which were widely shared by all political groups, received remarkable media coverage.

It also opened up prospects for the future by formulating a series of recommendations on strategic stockpile management and health governance, aimed at improving coordination between the State and the regions. Almost five years after these conclusions, what is the situation? Some of the recommendations have been taken into account, but it must be said that monitoring the implementation of these recommendations - which can take a very long time - remains a challenge. I know how committed you are to monitoring these recommendations over time, and I therefore hope that your discussions will result in proposals to this effect.

The coronavirus epidemic is fortunately over, but parliamentary committees of inquiry remain at the forefront of current affairs. In France in particular, several committees of inquiry have been the subject of intense media coverage in recent months, such as the Senate committee on the practices of bottled water manufacturers and, in the National Assembly, the committee of inquiry on the prevention of violence in schools, which heard from Prime Minister François Bayrou. The days when, according to Georges Clemenceau, “the best way to bury a scandal in politics is to set up a committee of inquiry” are now over. This is to be welcomed.

However, criticism and even controversy are emerging: some commentators and politicians believe that there are now too many committees of inquiry, while others feign outrage in the press - with inevitable ulterior motives - about the “trap” that parliamentary committees of inquiry have become for business leaders. Furthermore, certain public figures have recently refused to appear before committees of inquiry, even though they are required by organic law to comply with the summons issued to them.

This situation is regrettable because parliamentary committees of inquiry are one of the main means of scrutinising the Government's actions. This instrument must be used to promote democratic control. I believe that the best way to put an end to these controversies is to continue, more than ever, to demonstrate seriousness and rigour in our work, in a spirit of cross-party cooperation that transcends political divisions. To cite once again my experience on the committee of inquiry into the Covid-19 pandemic, I served as rapporteur alongside two other colleagues from other political groups. This enabled us to establish shared findings and reach consensual conclusions. I believe that this is part of our `trademark' in the Senate.

In light of these news, I would like to conclude by emphasizing the usefulness of your upcoming discussions on the legal frameworks and practices of parliamentary committees of inquiry in your respective countries. It is true that our institutions operate within very different constitutional frameworks, but committees of inquiry are a widely used instrument of oversight. Your discussions will undoubtedly help to shed light on our own practices and identify good practices that will be useful to all and which, I hope, will inform the next `batch' of committees of inquiry arising from the drawing rights next autumn.

Before giving the floor to the Secretary General of the Senate, I would like to thank you all for your participation and wish you an excellent seminar.

2. Mr Éric TAVERNIER, Secretary General of the Senate

Madam President,

Ladies and gentlemen,

Dear colleagues,

Thank you all for responding positively to our invitation. I would particularly like to welcome two colleagues from the Ukrainian Rada, with which the Senate enjoys an active working relationship. I would also like to thank the ECPRD secretariat and the coordinator for parliamentary procedure and practice, Mr Christoph Konrath, for their support in organising this seminar.

Madam President, you rightly emphasised the usefulness of the ECPRD network for inter-parliamentary cooperation and information sharing. I would add that this is particularly true in the field of parliamentary law and procedure, as there is little academic literature or public information with a comparative dimension in this area. The direct exchange of information between practitioners is therefore essential, and I hope that it will also enrich our exchanges with the academic community, to which I am personally and professionally very attentive and which I am committed to developing. That is the raison d'être of today's meeting.

Madam President, you also mentioned the current situation regarding parliamentary committees of inquiry and their importance for the Senate. In this regard, allow me to give a brief historical overview, as we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Republican Senate this year. The Senate has contributed significantly to the development of committees of inquiry in France, particularly during the Vth Republic.

The first committees of inquiry in France can be traced back to the establishment of a parliamentary system. After the great French Revolution, followed by a Napoleonic episode, and finally after the return of the Bourbons, it was in 1832, under the July Monarchy, that the Chamber of Deputies arrogated to itself, without any textual basis, a "right of inquiry" and, in doing so, created a committee of inquiry into the deficit of the central cashier Mr Kessner. Some historians also see in the trials of the Chamber of Peers - the predecessor of the Senate - when it was constituted as a High Court, a form of parliamentary inquiry emerging, particularly during the trial of Charles X's former ministers in 1832. On the basis of this customary creation, committees of inquiry then multiplied under the IIIrd Republic: from 1876 to 1878, the Senate created a committee of inquiry into “railways and the suffering of trade” and, in 1886, another on alcohol consumption.

However, it was not until the eve of the First World War that the so-called “Rochette Law” [law of 25 March 1914] - following the financial scandal of the same name - provided a legislative basis for the investigative powers of the committees of inquiry of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.

The IVth Republic continued the rules and practices of the previous regime with regard to committees of inquiry. The Council of the Republic - the name given at the time to the upper house - introduced the right of inquiry into its rules of procedure in 1947 and set up committees of inquiry into the economic situation in the overseas territories (1952) and the wine scandal (1949) in order to “verify” the conclusions of the National Assembly's report on the subject.

However, the 1958 Constitution, in line with General de Gaulle's institutional concepts, marked a desire to break with the “excesses” of parliamentary committees of inquiry under previous regimes. In the early days of the Vth Republic, parliamentary committees of inquiry had strictly limited powers: those summoned were not legally obliged to appear before a committee of inquiry, hearings were secret and the report was not published (unless the assembly authorised it by a vote). The Senate, where the Gaullist party did not have a majority at the time, nevertheless launched committees of inquiry into burning issues: in 1961, on the events in Algeria, then on the “events of May 1968”.

But in the absence of binding investigative powers, their results were meagre. Thus, in 1967, the Senate committee of inquiry into the French Radio and Television Office (ORTF) was refused permission to hear a whole series of directors. ORTF employees were even threatened with sanctions by their director general if they answered questions posed by members of the committee.

It was on the initiative of the Senate that a bill was passed in 1977 to extend the powers of parliamentary committees of inquiry: their maximum duration was increased from four to six months, rapporteurs were given the right to investigate documents and conduct on-site inquiries, and the principle of public disclosure of reports was affirmed. The same law also created an obligation to appear before committees of inquiry under oath, on pain of criminal prosecution. Then, in 1991, the publicity of hearings was authorised.

The 2008 constitutional reform finally enshrined the role of committees of inquiry: in order to enhance the role of Parliament, it enshrined in the Constitution the possibility of “creating committees of inquiry within each assembly to gather information, under the conditions laid down by law”. Since then, the Senate has made full use of this “drawing right”, as illustrated in particular in 2018 by the committee of inquiry into the so-called “Benalla affair” - concerning the actions of a special advisor to the President of the Republic - and the committee of inquiry into the use of consulting firms in 2022. Should this be seen, as Professor Jean-Éric Gicquel points out in his note published in the Dictionnaire encyclopédique du Parlement, as the consequence of the Senate's “possible misalignment” with the majority bloc?

The Senate therefore does not hesitate to defend this right of inquiry when it is undermined: on several occasions, and most recently in May 2025 concerning a Nestlé Waters executive, the Senate Bureau referred the matter to the Public Prosecutor's Office for perjury. Although these reports are often dismissed without further action, in 2018, a doctor who had concealed his links with the company Total when he was heard by the Senate committee of inquiry into the economic and financial cost of air pollution was fined €20,000 for perjury on appeal. He was in a clear conflict of interest.

It is striking to note that more than 200 years after the first committees of inquiry, investigative powers remain essentially the same. In his “Treatise on Political, Electoral and Parliamentary Law”, first published in 1878, Eugène Pierre cites among the powers of “parliamentary inquiries” the right to summon witnesses, request documents and conduct hearings. However, investigation methods and techniques have been refined. Moreover, with the development of digital technologies, social networks and now artificial intelligence, will the use of these investigative powers not evolve?

One of the objectives of this seminar is precisely to stimulate reflection on the current and future development of our investigation techniques and methods. It also aims to compare our respective legal frameworks with the practical experience of committees of inquiry and to foster reflection on our procedures. Hence our decision to focus this seminar firmly on the “practice of parliamentary committees of inquiry”, in the fervent hope that we will be able to improve them even further, as Chairwoman Vermeillet mentioned just now.

After today's introductory session, which will give you an overview of the different models of committees of inquiry, tomorrow's programme will be organised around the following four themes:

- the first session will deal with committees of inquiry as a tool for controlling the executive, including a discussion on the balance between the majority and the opposition and the role of the upper houses;

- the second session will focus on investigative powers, methods and techniques;

- the third session will address collaboration and conflicts between committees of inquiry and other institutions, particularly the judiciary;

- finally, the issue of the outcomes and follow-up to committees of inquiry will be the subject of discussion groups, during which you will be able to exchange views on best practices in terms of monitoring recommendations and communication.

Speakers from nine different parliamentary assemblies will take turns sharing their experience and expertise on these various topics. I would like to express my warmest thanks to them. I have no doubt that these presentations will fuel fascinating discussions, and I look forward to reading the reports with great interest.

I wish you a very successful seminar and hope that your discussions will be as rich as they are stimulating.

C. OPENING SESSION: OVERVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES OF INQUIRY (PCIS) IN ECPRD MEMBER PARLIAMENTS

During the opening session, Ms Anne-Céline Didier, Head of the Comparative Law Unit and ECPRD correspondent (Senate - France), and Mr Christoph Konrath, Coordinator of the ECPRD's Parliamentary Procedure and Practice Area (Nationalrat - Austria), presented the various models and legal frameworks for parliamentary committees of inquiry (PCIs) among the ECPRD countries (see the presentation in the annex).

Introduction

As a preliminary point, it is worth highlighting a paradox: although parliamentary committees of inquiry (PCIs) are widespread and generally recognised as one of the most powerful instruments of parliamentary control over the executive, the literature devoted to them remains relatively limited, particularly from a comparative perspective. When it does exist, this literature most often focuses on only two or three countries, without offering a broad overview. This observation calls for an attempt to define the concept of a parliamentary committee of inquiry. However, there is no single definition that applies across all parliaments.

In his book on parliamentary law, constitutionalist Jean-Éric Gicquel defines parliamentary committees of inquiry as emanations of assemblies, established to gather information on specific facts or on the management of public services, in order to enable Parliament to fully exercise its role of overseeing government action.

Conversely, from a comparative perspective, Elena Griglio, an official at the Italian Senate, proposes in her book on parliamentary oversight a broader definition of committees of inquiry, which she describes as temporary bodies set up within a legislature to investigate specific issues.

The scope covered by committees of inquiry appears to be very broad . In the sources analysed, the most frequently mentioned concept is that of a “subject of public interest”. In principle, the committee must focus on a subject of general interest, but this requirement is rarely defined precisely, which contributes to significantly broadening the scope of possible investigations.

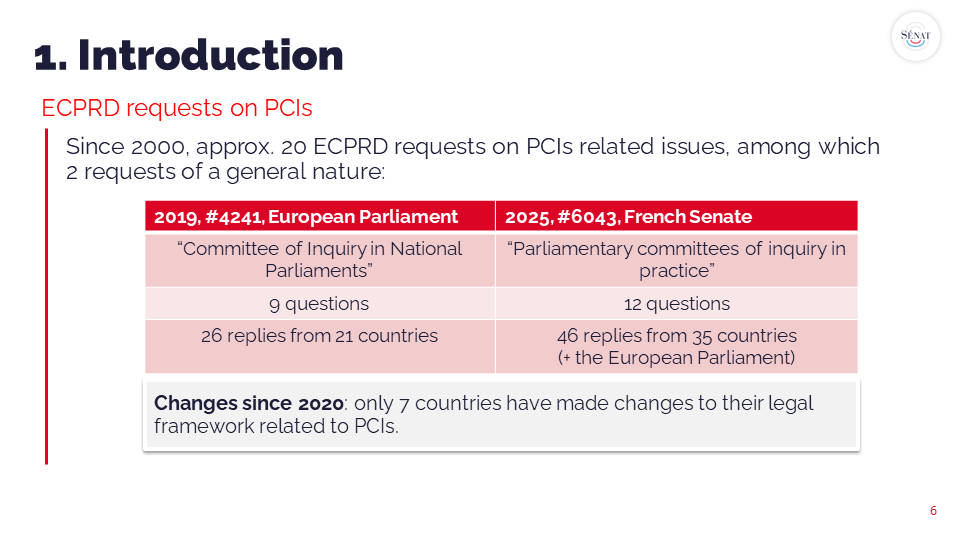

To prepare this conceptual introduction, we relied mainly on responses to questionnaires sent to the ECPRD's members. Since the 2000s, some twenty requests addressed to this network have dealt, directly or indirectly, with committees of inquiry, most often concerning specific procedural issues, such as the hearing of witnesses. Among these, only one major request --issued by the European Parliament in 2020-- provided an overview of the situation, which then gave rise to a study. This request comprised nine questions and received 26 replies from 21 countries. On this basis, a few months ago we sent out a request containing twelve questions, partly intended to update the existing data. We received 46 answers from 35 countries, plus the European Parliament. The responses from the previous study were incorporated into our analysis. From a legal perspective, only seven countries have amended their framework for committees of inquiry since 2020.

General overview and attempt at classification

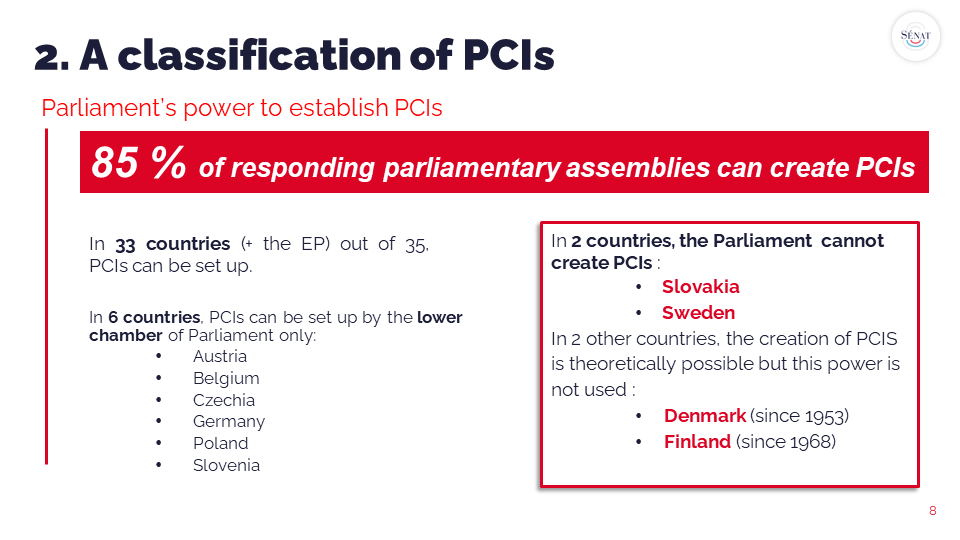

In the vast majority of cases, parliamentary assemblies have the power to set up committees of inquiry. In our study, 85 % of the assemblies that responded to the questionnaire indicated that they had this prerogative, representing 33 countries, plus the European Parliament.

In some parliamentary systems, however, a distinction is made between the two chambers. In six countries - namely Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovenia - only the lower house is empowered to establish a committee of inquiry. There are also two special cases: Slovakia and Sweden, where parliaments do not have the power to set up such committees.

There are also intermediate situations in some countries where, although the establishment of committees of inquiry is legally possible, it is not implemented in practice. Denmark and Finland are two examples of this. In its responses to requests from both the European Parliament and the French Senate, Denmark indicated that this possibility exists constitutionally, but that no parliamentary committee of inquiry has been established since 1953. In Finland, no use has been made of this possibility since 1968.

As for Sweden, although it does not formally provide for the creation of parliamentary committees of inquiry - this prerogative belongs exclusively to the Executive - its constitutional commission has extensive investigative powers, particularly with regard to access to information. This case may therefore be subject to some nuance in the classification.

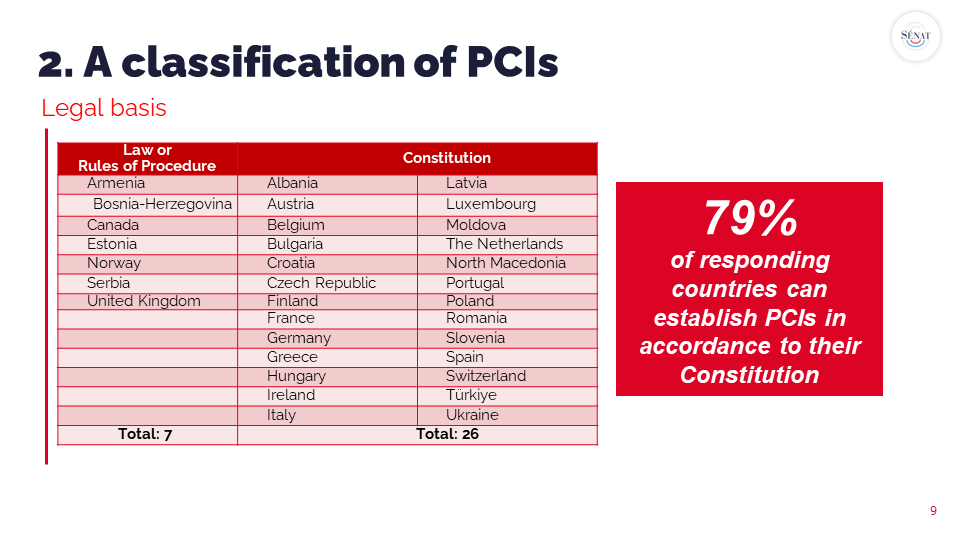

In nearly 80% of the countries that responded to our questionnaire, the power to establish committees of inquiry is based on constitutional provisions. In a smaller number of states, this power is regulated by law. Only one country, Estonia, bases it exclusively on the rules of its assembly.

Specific cases

Certain specific cases make it difficult to establish a strict typology, as institutional configurations can vary greatly.

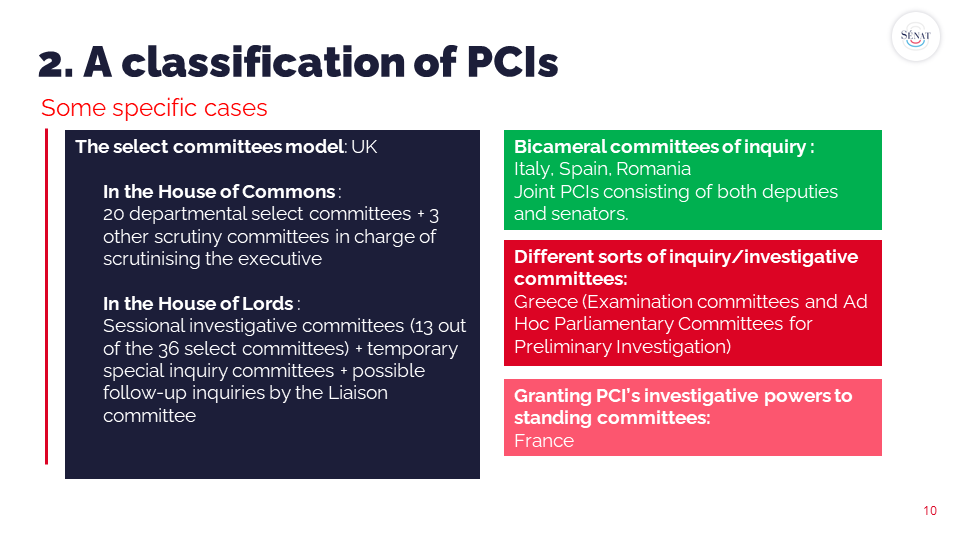

The United Kingdom stands out for its use of select committees, permanent committees with a supervisory role, whose powers can be as extensive as those of committees of inquiry. In addition, the House of Lords has the option of setting up special investigative committees, which are temporary in nature and more similar to the committees of inquiry found in other countries.

Another interesting configuration is that of certain bicameral systems - notably Italy, Spain and Romania - where it is possible to create not only committees of inquiry specific to each chamber, but also committees common to both assemblies.

In Greece, two types of committees of inquiry coexist: examination committees and ad hoc commissions, which are mainly responsible for conducting preliminary investigations into politicians.

Finally, in some parliaments, it is possible to grant standing committees the same powers as committees of inquiry. This practice is becoming more common in France.

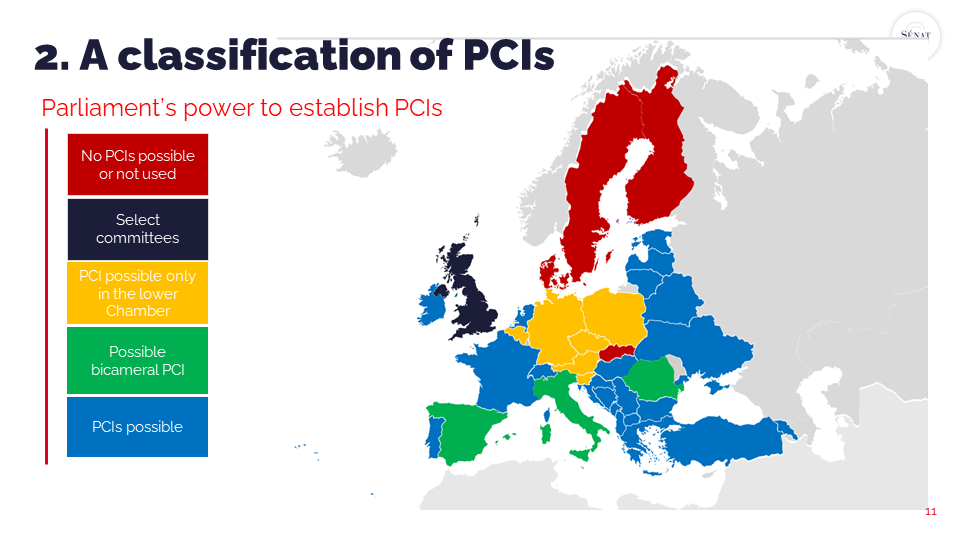

These different configurations have led us to develop a typological map distinguishing between the situations observed. Countries where parliament does not have the power to set up committees of inquiry or does not exercise this power in practice are shown in red; in yellow, the states where this prerogative is reserved for the lower house; in green, the bicameral systems allowing the creation of joint committees of inquiry for both houses; in light blue, the countries where each house - in both unicameral and bicameral systems - can set up a committee of inquiry; in dark blue, the British case.

Frequency and Duration of Parliamentary Committees of Inquiry (PCIs)

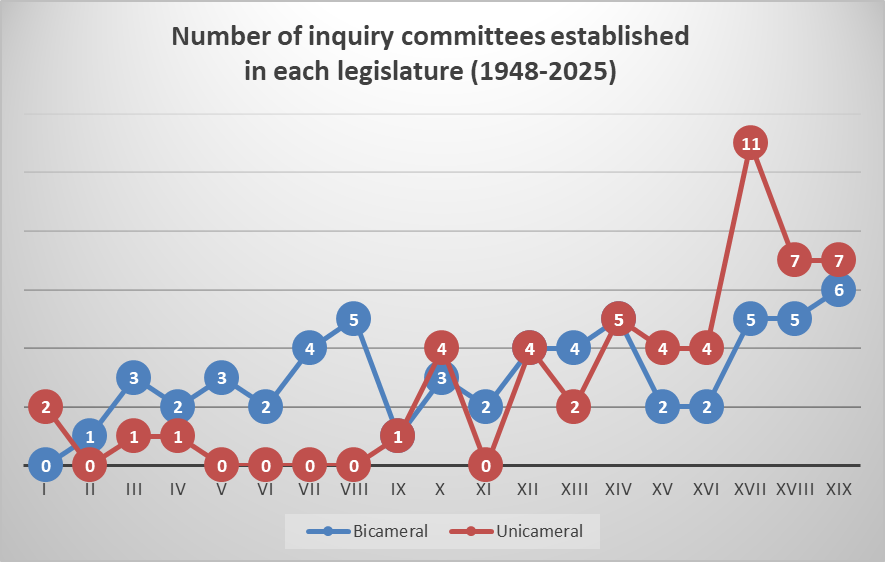

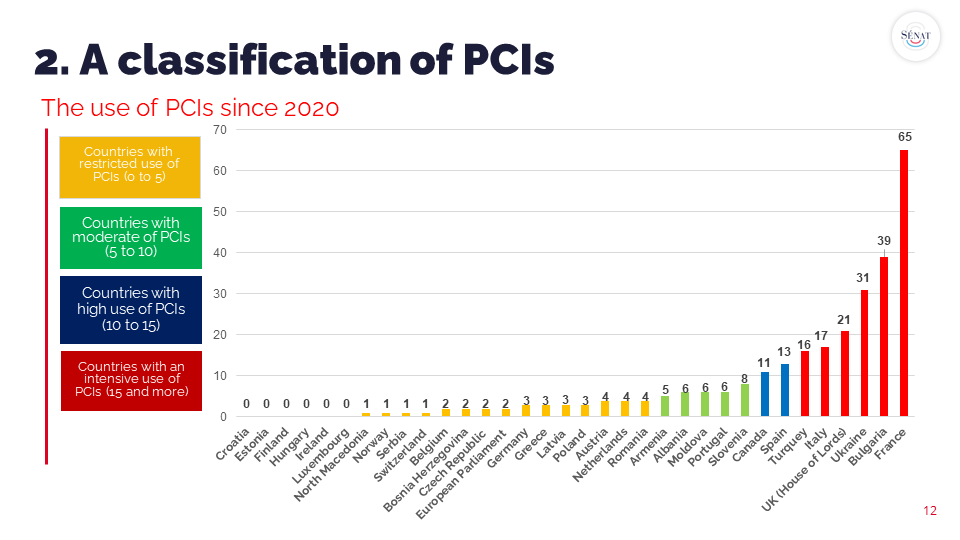

To provide a quantitative overview, we have taken 1 January 2020 as our reference date in order to avoid biases linked to the diversity of legislatures. The results show that France is clearly in the lead, with 65 committees of inquiry established since that date: 25 in the Senate and 40 in the National Assembly of Bulgaria and Ukraine follow.

Conversely, more than half of the countries established fewer than fifteen committees of inquiry during the same period, and six of them have not established any since 2020. These data confirm the wide diversity of practices between countries.

In the United Kingdom, it is difficult to produce comparable statistics, as many inquiries are conducted within the framework of select committees. The figure presented corresponds only to part of the House of Lords' inquiry activity and therefore does not reflect the entirety of parliamentary oversight work.

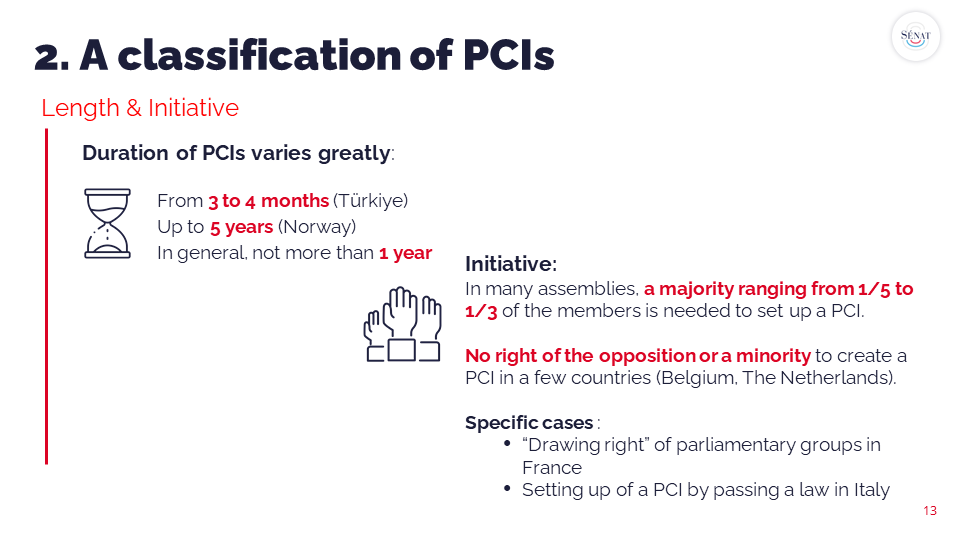

Comparing frequency of parliamentary committees of inquiry (PCIs) across countries is a complex task, given the wide variation in their duration. In some cases, inquiries are completed in a few months --three to four months in Turkey, for example-- whereas in others, such as Norway, proceedings may last up to five years. On average, however, most PCIs operate over a period of one to two years.

Initiation of a Committee of inquiry

The creation of a PCI presupposes a formal initiative. In most countries, parliamentary minorities now possess the ability to initiate a PCI --a prerogative often described as a form of “minority right.” The extension of this right is relatively recent, yet increasingly widespread. Many parliaments allow one-fifth, one-quarter, or up to one-third of their members to request the establishment of a PCI, with one-quarter being the most common threshold.

On the contrary, in Belgium and the Netherlands, minorities or opposition parties do not hold the right to initiate a PCI. In Austria, such a minority right was only introduced in 2015. Several specific cases stand out: in France, for instance, political groups have a “drawing right” to request a PCI; in Italy, a formal law must be passed to establish one. The actual use of this minority right varies significantly across countries --heavily relied upon in some, and rarely invoked in others.

Presidency of Committees of Inquiry

The question of who chairs a PCI is the subject of considerable debate. Should the chair remain neutral? Should they take an active role in steering the committee towards conclusions? Or might they use the position to advance their own political career?

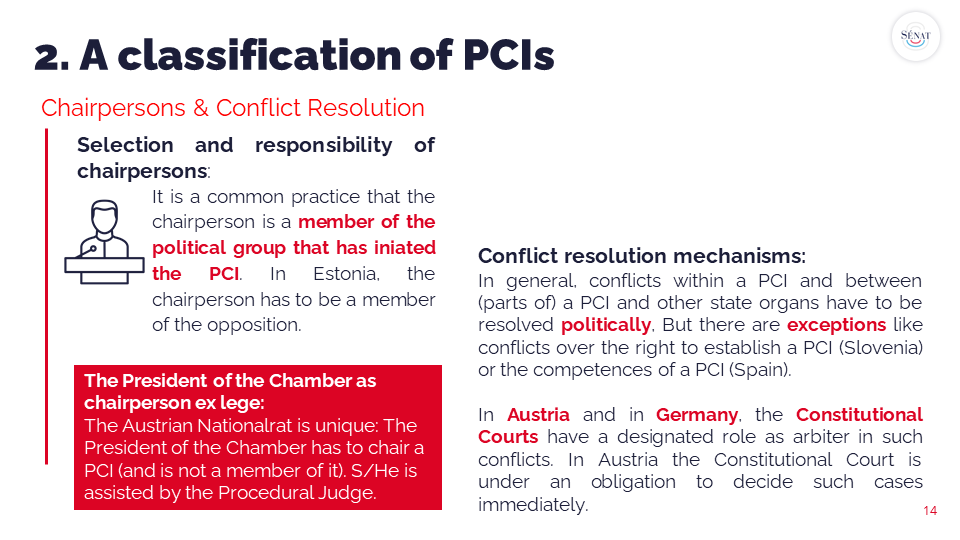

In most countries, the prevailing rule is that the chair is elected from among the members of the political group that initiated the PCI. Estonia provides an exception: the chair must be a member of the opposition. In Germany, the issue has long been debated, reflecting its institutional sensitivity.

Austria offers a unique arrangement: the President of the Chamber serves ex lege as chair of any PCI. This individual is not a committee member and acts as a neutral authority. Remarkably, the President does not act alone; they are supported by a procedural judge whose role is to safeguard the rights of witnesses and third parties potentially affected by the committee's work. This configuration appears to be unique in Europe.

Managing Conflict Within or Around a PCI

Disputes may arise both within PCIs and between a PCI and other state institutions. Generally, such conflicts are resolved politically. However, judicial interventions do occur. In Slovenia and Spain, for example, courts have ruled on matters related to the right to establish a PCI or on the scope of their competences. In Germany and Austria, numerous cases have been brought before constitutional courts to address disputes either internal to the committee or between the committee and other state bodies. These typically concern the obligation to transmit documents or the classification of information. In Austria, individuals affected by the work of a PCI may apply directly to the Constitutional Court. Some of these cases will be discussed in greater detail tomorrow.

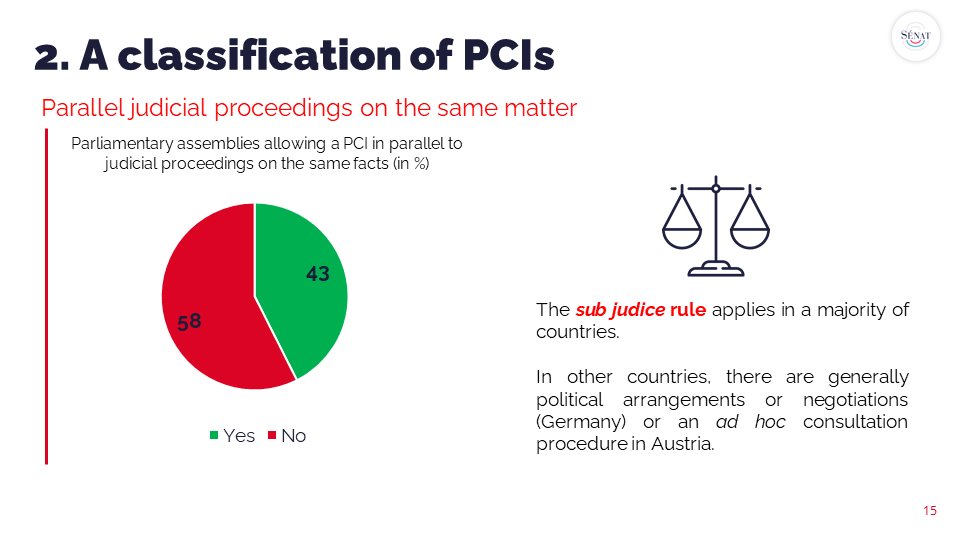

PCIs and Judicial Proceedings

PCIs are frequently likened to judicial proceedings, a comparison sometimes reinforced by how they are portrayed in the media --even the physical arrangement of seating can evoke a courtroom. Nevertheless, most parliaments maintain a strict separation between parliamentary and judicial processes, affirming that the two should not occur concurrently.

Almost ten years ago, however, the European Court of Human Rights2(*) issued a landmark decision in a Polish case, finding that judicial and parliamentary proceedings follow distinct logics and can, therefore, proceed in parallel. This decision invites further reflection on how such overlaps can be managed in practice.

Germany's Bundestag has developed informal mechanisms of negotiation to manage potential conflicts. In Austria, a formal consultation procedure exists, involving both the federal Minister of Justice and the parliamentary committee. In the United Kingdom, the sub judice rule serves as a prototypical safeguard, designed to prevent simultaneous parliamentary and judicial proceedings on the same matter.

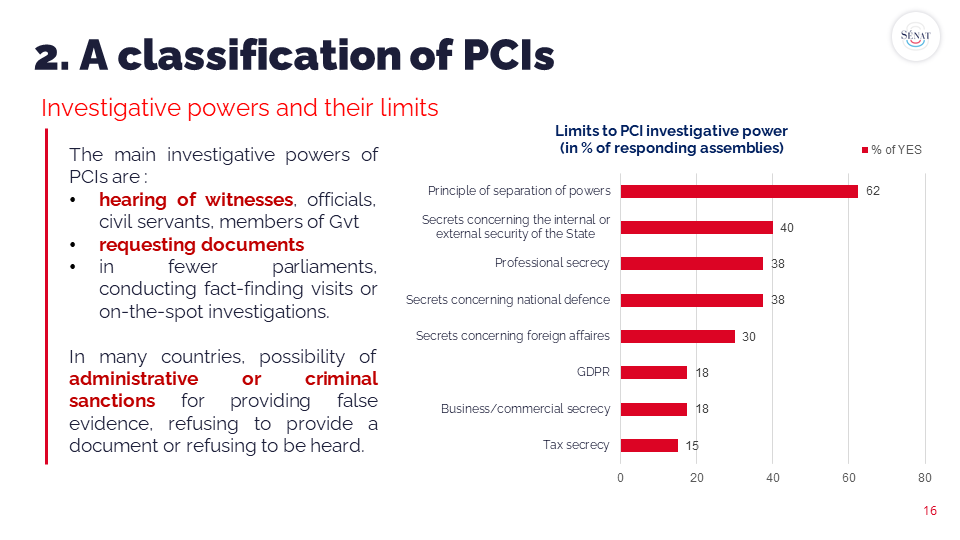

Powers of Committees of Inquiry

The core powers vested in PCIs are relatively consistent across jurisdictions: they include the ability to summon and hear witnesses --usually public officials-- request documents, and conduct fact-finding missions.

Nevertheless, some divergences exist, particularly regarding the actual enforcement of cooperation. For example, procedures and sanctions related to witnesses refusing to testify or withhold documents differ among states. Another key area of divergence concerns the treatment of sensitive or classified information, and the extent to which PCI members may rely on such material in their reports or subsequent political actions.

Over the past years, additional concerns have emerged regarding data protection and the applicability of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). A judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union concerning Austria established that PCIs are subject to the obligation to protect personal data. This has significant implications not only for the hearings themselves, but also for the drafting of reports and the broader political use of their findings. These issues warrant careful discussion.

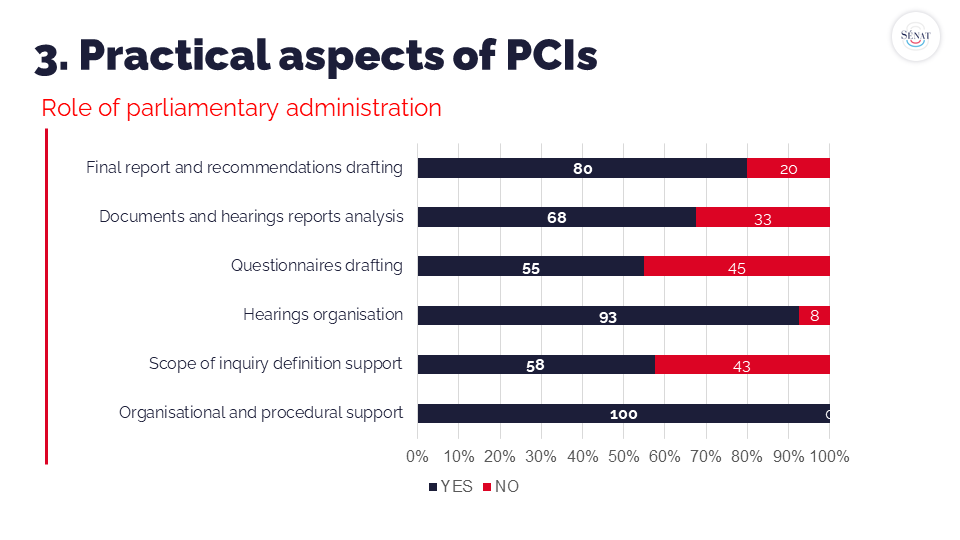

The role of parliamentary administration

Our survey shows that, in the vast majority of cases, parliamentary administration is closely involved in the work of parliamentary committees of inquiry. In all of the parliaments surveyed, it provides at least logistical and organisational support to the committees.

In more than half of the cases, the administrative services also participate in defining the precise scope of the inquiry. In two-thirds of the assemblies, they take part in analysing the documentation collected, or even conduct the analysis themselves. Their involvement can extend to drafting the final report, or even the recommendations themselves.

On the other hand, fewer responses mention the administration's contribution to the drafting of questionnaires. This may come as a surprise, particularly in view of French practice, where the drafting of questionnaires is common.

Finally, in all parliaments, the administration plays a supporting role in procedural matters. It ensures compliance with the legal framework applicable to committees of inquiry and, in most cases, acts as a point of reference for the interpretation of the constitutional or regulatory rules governing their work.

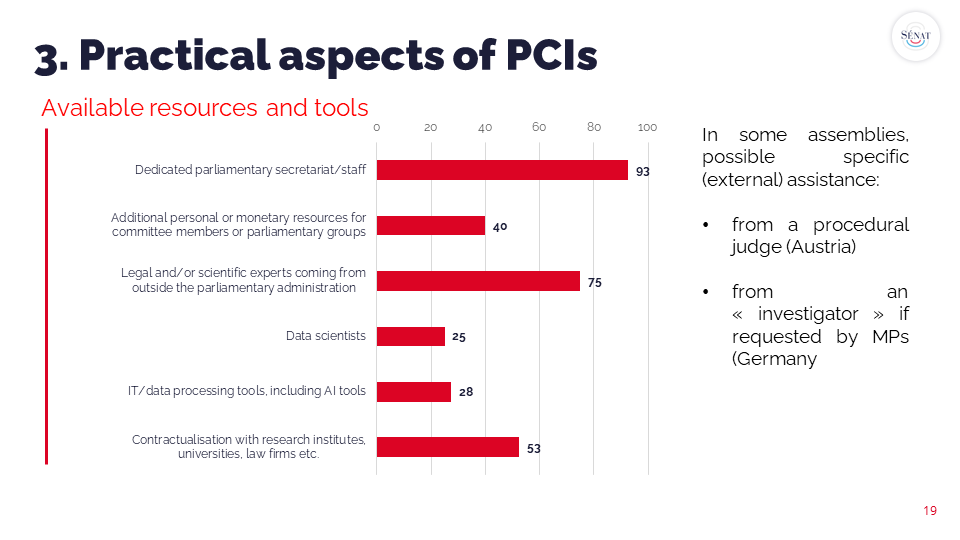

Resources and tools available to committees of inquiry

In most assemblies, committees of inquiry have their own secretariat, composed of civil servants or parliamentary staff. In 93 % of cases, a dedicated administrative structure is put in place.

Many parliaments also provide additional human resources, particularly through political groups. External legal or scientific experts are frequently called upon. These experts may be engaged on an individual basis or under contracts with research institutes or academic centres.

However, only a quarter of parliaments report using data experts to process large volumes of information, particularly digital data such as mass emails. The use of data processing tools, including artificial intelligence tools, remains marginal: only 28 % of the parliaments surveyed reported using them.

Finally, certain national configurations have notable specificities. In Austro-Germanic systems, there is formalised use of external expertise: in Austria, for example, a procedural judge assists the committee in its work; in Germany, it is possible to call on an external investigator.

D. SESSION 1 - PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES OF INQUIRY AS A TOOL OF SCRUTINY OF THE EXECUTIVE

1. Parliamentary inquiries in Ireland: an overview of legal and structural challenges, Mrs Cathy EGAN (Houses of the Oireachtas - Ireland)

The central theme of today's discussions is whether parliamentary committees of inquiry are effective tools for scrutinising the executive.

In this contribution, I will outline the historical and legal background that has shaped the current framework, present the experience of the banking inquiry as a test case under the new legislation, examine the legal and operational challenges encountered, and finally reflect on the lessons learned and the legacy of that process.

Since the foundation of the Irish state, parliamentary inquiries have been rare. Fewer than a handful were conducted prior to the 2000s. One significant turning point was the Abbeylara case3(*). It led to the establishment of a parliamentary inquiry, tasked, among other things, with examining the conduct of the Gardaí and assessing whether the situation could have been handled differently.

This inquiry was legally challenged by the police, who argued that any determination of wrongdoing on their part should be made by a court of law, not by a parliamentary body. In its Abbeylara judgment delivered in 2002, the Irish Supreme Court ruled that the Houses of the Oireachtas --the Irish Parliament-- do not possess an inherent constitutional power to make findings that impugn the good name of individuals. According to the Court, such determinations fall exclusively within the jurisdiction of the judiciary. The Abbeylara decision effectively brought an end to parliamentary inquiries in Ireland for more than a decade.

In response, the government sought to amend the Constitution to enable the re-establishment of robust parliamentary inquiries. However, the proposed constitutional amendment was rejected by referendum in 2011, following a campaign marked by strong and vocal opposition. Prominent legal figures warned against the risks of excessive parliamentary power. The referendum failed.

As a result, the government was compelled to work within the existing constitutional parameters. These efforts culminated in the enactment of the Houses of the Oireachtas (Inquiries, Privileges and Procedures) Act 2013, hereafter referred to as the Inquiries Act. This legislation established a statutory framework allowing for five distinct types of parliamentary inquiry:

1. inquiries into legislative matters --aimed at determining whether new legislation is required in a particular domain;

2. inquiries to remove officeholders --for example, to assess whether a judge should be removed;

3. inquiries into the conduct of designated officeholders --such as evaluating the performance of a Secretary General of a government department;

4. inquiries into the conduct of members of the Oireachtas --dealing with disciplinary or ethical issues involving parliamentarians;

5. general inquiries under Section 7 --the broadest and most flexible category, allowing an inquiry into any matter. These are commonly referred to as “Inquire, Record, Report” inquiries.

Of these five types, the first --legislative inquiries-- is of limited practical interest and is rarely used. The others are more substantive but focus on narrowly defined individuals or circumstances. The fifth category, under Section 7 of the Act, is the only one that permits inquiries into general public interest matters. It offers the widest scope but still operates within the tightly drawn limits of the constitutional framework defined by the Abbeylara decision.

The most significant function of a parliamentary inquiry conducted under Section 7 of the Inquiries Act is the ability to issue findings that a particular matter --relating to systems, practices, procedures, policies, or the implementation of policies-- ought to have been conducted differently. For instance, a finding might state that a regulator who had the legal authority to enforce limits on spending should have exercised that power.

The only inquiry conducted under the Inquiries Act to date was the Committee of Inquiry into the Banking Crisis, which served as a real-life test of the Act's provisions. It operated between late 2014 and early 2016, with a mandate to investigate the causes of Ireland's systemic banking collapse. I was part of the dedicated administrative team, composed of 57 full-time staff members, assigned to support the work of the committee over this period.

The inquiry represented a substantial institutional effort: it cost over €6.5 million, involved public hearings with 131 witnesses, and entailed the review of more than 500,000 pages of documentation.

As a Section 7 “Inquire, Record, Report” inquiry, the banking committee was tasked primarily with recording evidence and reporting on its findings. However, it had only limited authority to draw factual conclusions. Under the Act, the committee was prohibited from making any finding of fact if the evidence supporting it was contradicted by other testimony.

It is unlikely that a Section 7 inquiry would ever result in a formal finding against an individual. Nonetheless, the Act requires that all inquiries --regardless of their type or legal scope-- adhere to the same stringent procedural safeguards. This includes, in particular, the obligations set out in Section 24 concerning fair procedures.

Strict rules also applied to potential perceptions of bias. Any suggestion of partiality could result in the removal of a committee member. This required us to train members to adopt a neutral and cautious approach during hearings, avoiding adversarial questioning or “gotcha” moments. Public appearances by members were also restricted throughout the inquiry's duration --an unusual constraint in a political setting.

This structural flaw, embedded in the legislation itself, imposed significant operational burdens on the inquiry from the outset. In addition to these systemic constraints, the banking inquiry faced a number of unique challenges that may not arise in future inquiries --most notably, the issue of time pressure and political risk.

As the first inquiry conducted under the Act, we were tasked with designing the entire process architecture. However, no preparatory period was allocated prior to the commencement of the inquiry. Political urgency dictated a rapid launch, and we were compelled to build procedural frameworks on an ad hoc basis while the inquiry was already underway.

The committee formally began its work in December 2014. Under the rules governing our parliamentary system, the Dáil (lower house) could not remain in session beyond early March 2016. However, the decision to dissolve Parliament lies with the Taoiseach and can be taken at any moment -- typically at a time deemed politically advantageous, and not necessarily at the end of the full term.

In our final report, we included a proposed model for how future parliamentary inquiries in Ireland should be conducted. The key recommendation was a sequential and clearly delineated process, with each phase --preparation, investigation, hearings and reporting-- allocated sufficient time and resources. We advocated a minimum two-year timeline to enable proper execution of these stages, rather than overlapping all elements simultaneously as we had been forced to do.

If another inquiry were to take place in future, it would at least benefit from the framework, documentation and templates we developed. While now over a decade old, they remain a valuable point of reference.

A second major challenge encountered during the banking inquiry concerned the overlap with ongoing criminal proceedings. Several key individuals were at the time facing criminal charges related to the banking crisis. The Gardaí and the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) issued warnings that the inquiry's activities, particularly the taking of certain evidence, could jeopardise these criminal trials.

Another substantial difficulty arose from the belated discovery of Section 33AK of the Central Bank Act, which prohibits the disclosure of information held by the Central Bank. This statutory provision came to light only after the inquiry had already commenced, despite the centrality of Central Bank material to the subject matter under investigation. Emergency legislation was required to amend the provision. Even after the amendment, any material obtained under the revised provision was subject to strict confidentiality obligations. The inquiry was compelled to develop complex data segregation protocols, unanticipated at the outset, to ensure compliance.

One of the key recommendations for future inquiries is the early identification and resolution of any legal barriers to the production of evidence --a step that was unfortunately overlooked in this instance.

Jurisdictional limitations presented further obstacles. While Irish citizens and residents may be compelled to give evidence, many of the principal figures in the banking crisis --including advisers and decision-makers-- were foreign nationals. As such, the committee had no legal power to compel their cooperation.

Despite all these difficulties, the inquiry succeeded in publishing its final report. Volume I set out the committee's findings and the evidence supporting them; Volume II included 28 procedural recommendations for future inquiries. Chief among them was a call to amend the Inquiries Act to allow for a streamlined inquire-record-report procedure, with no authority to make findings against individuals --and accordingly, with proportionate procedural obligations. Other recommendations included a minimum two-year timeline for inquiries, comprehensive statutory auditing at the pre-inquiry stage to avoid unknown barriers (such as Section 33AK) and a clear protocol governing the relationship between the DPP and the Houses of the Oireachtas.

In conclusion, can parliamentary committees of inquiry serve as an effective instrument of scrutiny in Ireland? In theory, yes. But in practice, the current constitutional and statutory framework renders them rare, procedurally burdensome, and legally constrained --particularly when compared to ordinary committees vested with compellability powers. The recommendation for a simplified, lower-stakes form of inquiry is effectively a recommendation to return to those existing parliamentary committees.

2. Bicameral inquiry committees in the Italian experience,

Mr Luigi GIANNITI (Senato della Repubblica - Italy)

The investigative power of the Chambers is expressly envisaged in the Italian Constitution: according to Article 82, “Each House of Parliament may conduct enquiries on matters of public interest”. The second paragraph further establishes how this power is to be exercised: “An Enquiry Committee may conduct investigations and examination with the same powers and limitations as the judiciary”.

The constitutional framework refers to inquiry committees that `each Chamber' may set up, therefore implying that the committees may belong to either the Chamber or to the Senate. And yet, a frequent way in which the Italian parliament conducts enquiries is through bicameral committees. The reason lies in a characteristic feature of Italian bicameralism: Parliament is formed by two directly elected chambers, with substantially similar electoral laws, both of which give the government a vote of confidence and participate equally in the legislative function.

Inquiry committees as a choice of the majority

Bicameral committees are generally established by law, which helps to better clarify the powers of the committees themselves. The decision to set up an inquiry committee is adopted by majority. While the Constitution was being drafted by the Constituent Assembly, the possibility of setting up minority inquiry committees (as per the German model) was taken into consideration. Ultimately, this was not the choice.

Throughout the first phase of republican history, the decision to proceed with parliamentary enquiries was the result of a widely shared agreement among political parties. The first inquiry committees in the 1950s dealt with major issues of Italian society: poverty, unemployment, the condition of workers, hindrance to competition in the economy.

This instrument was therefore initially used by Parliament as an attempt to provide political and legislative answers to these problems, based on President Luigi Einaudi's motto “know in order to decide”.

Starting from the 1960s, investigations launched for legislative purposes were flanked by political enquiries into specific events. From then on, the question of the relationship between the exercise of parliamentary investigative power and the judiciary began to arise.

Bicameral vs unicameral committees

Tracing the history of the Italian Republic from 1968 to 1983, all inquiries were carried out by bicameral Committees: those were the years of the so-called `centrality of Parliament'.

The use of bicameral committees established by law to conduct inquiries was also a sign of the cohesion of the party system and its parliamentary representation.

In 1971 new parliamentary regulations were approved, which introduced fact-finding investigations. These became the standard tool used by committees (both permanent and temporary) to acquire knowledge on issues within their remit in a coordinated and systematic manner.

During the 10th legislature (characterized by high political mobility and lasting the entire constitutional term of five years, from 1987 to 1992), seven committees of inquiry were set up, the highest number to date. Four were single-chamber committees: three by the Senate, one by the Chamber.

The crisis of the so-called “Repubblica dei partiti” came to a head during those years. Significantly, during this legislature the then President of the Republic, Francesco Cossiga, warned of the risk of “disharmonious and therefore unproductive, if not downright harmful, activities”, in particular for inquiries concerning “matters on which judicial proceedings are still pending, in which it would be seriously improper to interfere, even de facto, with encroachments or inappropriate suggestions4(*).”

More recently, starting in 1992, unicameral committees reappeared (from 1994 to 1996, there were nine inquiry committees: four bicameral and five unicameral, including three in the Senate). Since then, single-chamber committees have outnumbered bicameral ones. The Senate often has more unicameral committees than the Chamber of Deputies. In the 17th legislature (2013-2018), there were fifteen inquiry committees, and in the 18th legislature (2018-2022), there were twelve (five bicameral, three in the Senate and four in the Chamber of Deputies). The overall impression is that political fragmentation translates into a greater number of inquiries (mostly conducted by a single-chamber).

Bicameral committees currently active in the Italian Parliament

In the current legislature, since 2022, fourteen committees have been established: six bicameral, two unicameral in the Senate and six unicameral in the Chamber of Deputies. This is despite a one-third reduction in the number of parliamentarians5(*).

There were 630 deputies and today there are 400, while the number of senators elected has fallen from 315 to 200, plus five senators for life.

Among the bicameral committees currently operating, three are continuing the work of committees established in the past and deal with general issues: fight against mafia, waste management and the issue of femicide (on the latter issue, the law has established a specific offence). As far as they are concerned, we may affirm that they are continuous parliamentary bodies which are constantly renewed at the beginning of each legislature. This element may be considered under a controversial light in terms of efficiency and opportunity since it amplifies the risks connected with permanent inquiry committees “with the same powers and limitations of the judiciary” (see below).

Three are new committees: two of them concern specific issues under judicial investigation that have had a major impact on public opinion (the disappearance of two girls in exceptional circumstances and a rehabilitation community for minors and disabled people), and the last one concerns the management of the health emergency caused by Covid pandemic. All were established by law.

Duration and changing responsibilities of inquiry committees

Some enquiries were limited to a single legislature. In other cases, committees entrusted with extremely arduous tasks have kept operating throughout multiple legislatures. In these cases, the instrument of the bicameral committee is always used.

One such committee is the one tasked to investigate mafia-related activities (anti-mafia committee), set up for the first time in 1962 (3rd legislature) and regularly confirmed since then, with responsibilities that have been consolidated over time.

Actual investigation activity is currently flanked with a parallel cognitive activity, even taking on policy-making and control functions. For example, Law No. 22/2023, which set up the Anti-mafia committee in the current legislature, tasked it with investigating the relationship between mafia and politics, also with regard to the formation of electoral lists. The committee may also request information from the national anti-mafia and anti-terrorism prosecutor and monitors attempts of mafia-related influence and infiltration in local authorities. This is quite evidence of the growing and relevant tasks assigned at the inquiry committees in recent times; moreover, such kind of peculiar powers and prerogatives tend to expand the tendency to become more autonomous with respect to the Chambers themselves.

Limits of political nature: parliamentary enquiries and the judiciary

One problematic aspect concerns the limits of the powers of inquiry committees. Under article 82 of the Constitution, as mentioned above, the committee “may conduct investigations and examination with the same powers and limitations as the judiciary”.

The tools made available to this parliamentary body are therefore essentially those of the criminal investigation. In addition, more informal tools, such as hearings, can be used.

Since the 10th Legislature, i.e. since the end of the 1980s, the problem of the relationship between parliamentary inquiries and judicial proceedings has arisen on several occasions.

Inquiries were established and conducted simultaneously with ongoing judicial proceedings.

One such occurrence resulted in a case of conflict of attributions and a ruling by the Constitutional Court (Judgment No 26 of 2008).

As a deterrent, many laws establishing inquiry committees precluded the adoption of “measures concerning the freedom and secrecy of correspondence and any other form of communication, as well as personal freedom”6(*).

Another problematic issue has been the attempt by the current majority to condemn the actions of government officials of previous legislatures through the activity of inquiry committees. On several such occasions, the opposition not only voted against the draft bill establishing the inquiry committee, but even tried to slow down its activities.

Inquiry committees, just like judicial authorities, can order searches and seizures. These actions, being invasive of personal privacy, must be justified by specific investigative needs. Furthermore, they must be carried out in compliance with both the rules of the code of criminal procedure governing evidence gathering and the guarantees protecting the suspect, also at the constitutional level. Further limits on the use of these instruments appear to derive from the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms insofar as no means or remedies appear to be in place in order to challenge the legitimacy of seizures and searches ordered by inquiry committees before an independent and impartial authority7(*).

3. Parliamentary committees of inquiry and the “drawing right” in the French Senate, Mr Jean-Pascal PICY, Senior advisor at the Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee (Sénat - France)

Last year, I had the opportunity to serve as Head of Secretariat for the parliamentary committee of inquiry (PCI) on TotalEnergies, a major French electricity and gas company. This assignment was all the more interesting as the committee had been established at the initiative of the opposition. This highlights a distinctive feature of the French parliamentary system --one that notably differs from the Italian model. Since the 2008 constitutional reform, each political group belonging to the opposition is entitled to set up and lead one PCI per year in both the Senate and the National Assembly.

Today, I would like to provide an overview of how PCIs function in practice within the French Parliament. This includes a presentation of their legal framework, the practical conditions under which they operate, the methods and techniques they use, and the outcomes and follow-up mechanisms associated with their work.

Three types of legal instruments structure the legal framework governing PCIs in France. Notably, the Constitution only began to refer to PCIs relatively recently. While the current Constitution dates back to 1958, it was not until the constitutional revision of 2008 that Article 51-2 was introduced, providing that committees of inquiry may be established within each house of Parliament to gather information. Initially, the 1958 Constitution had sought to rationalise parliamentary powers and had significantly restricted the use of inquiry committees. However, legislative developments and evolving parliamentary practice have gradually expanded their use, and they now constitute an important instrument for strengthening parliamentary oversight.

Prior to the 2008 reform, only the 1958 Institutional Act regulated the establishment and functioning of PCIs. Under this framework, each chamber of Parliament may create its own PCI. Unlike in Italy, bicameral committees of inquiry are not permitted in France. The purpose of a PCI is to collect information either on clearly defined facts or on the management of public services or publicly owned companies. Not every subject proposed by a Member of Parliament qualifies as a legitimate basis for inquiry; the scope is strictly limited by law. Furthermore, PCIs cannot be established in relation to facts that are or have been the subject of judicial proceedings, in accordance with the constitutional principle of separation of powers.

The composition of each PCI reflects the political balance of the chamber to which it belongs. PCIs are temporary bodies, with a statutory duration limited to six months. However, the establishment procedure alone often takes at least one month, further reducing the effective time available for the inquiry itself. Within this limited timeframe, the committee conducts mandatory hearings. Persons summoned to testify are legally obliged to attend. In practice, however, individuals often initially resist these summonses, citing scheduling conflicts, technical obstacles or general inconvenience. It is usually at that point that they are reminded of the possibility of police enforcement to compel their attendance --a highly effective deterrent. As a result, summoned individuals almost always comply.

Witnesses are required to testify under oath, and they are explicitly informed that both perjury and any act undermining the solemnity of the proceedings constitute criminal offences. This obligation helps to ensure that witnesses take the hearings seriously.

Since 1991, the principle of public hearings has become the norm, enabling the media to cover and report on the work of PCIs. Certain hearings, however, may be held in closed session when classified or confidential information is discussed. Another essential prerogative of PCIs is the investigative power conferred upon the rapporteur, which includes the authority to conduct on-site inspections and to access documents. The prospect of a surprise visit by senators --often accompanied by members of the press-- to seize documents exerts considerable pressure on targeted entities. Consequently, the threat of legal action is usually enough to secure the cooperation of those who have been summoned or are under investigation.

There are two distinct procedures by which a parliamentary committee of inquiry may be established in France. The first is the standard procedure, which has been in place since 1958. Under this process, senators first draft a resolution to propose the creation of a PCI. This resolution is submitted to the standing committee responsible for the subject matter. Following this initial review, the Law Committee must verify that no legal proceedings are ongoing or have taken place concerning the same facts. Finally, the resolution must be adopted in plenary session by the Senate. Once adopted, the committee is officially created and its members are appointed. Each PCI may comprise up to 23 members.

The second mechanism, introduced by the 2008 constitutional reform, is the so-called drawing right (droit de tirage). This procedure acts as a sort of fast track, allowing each political group to establish one PCI per year. In this case, the resolution is not submitted to the relevant standing committee but is still subject to review by the Law Committee, which must confirm the absence of past or pending judicial proceedings. Unlike the standard procedure, there is no plenary vote; the President of the Senate simply acknowledges the establishment of the committee. This accelerated process grants the opposition a significant instrument of control, as the majority cannot block the creation of a PCI exercised under the drawing right.

Since 2009, PCIs established under the drawing right have often focused on sensitive or controversial issues. Typically, these committees are chaired by a member of the majority, while the rapporteur is appointed from the opposition --the political group that initiated the PCI. This configuration often results in a confrontational tone and heightened media attention. While such PCIs serve to increase public awareness of parliamentary oversight, they may also raise concerns about the politicisation of inquiries. A notable example occurred last month, when the Prime Minister, Mr François Bayrou, was heard for over five hours by the National Assembly in a PCI on violence against young people in schools, including the widely publicised Bétharram case. Some observers criticised the event as resembling a political trial rather than a neutral inquiry.

The composition of a PCI follows proportional representation. Members collectively designate both the chairperson and the rapporteur, each of whom exercises considerable authority. The chairperson is responsible for convening meetings of the committee and its bureau, signing summonses to hearings, and --where necessary-- employing coercive measures to secure attendance. The chairperson also presides over hearings and may initiate proceedings in cases of false testimony. The rapporteur has precedence in questioning witnesses and bears responsibility for drafting the final report. Given the complementary yet distinct nature of their roles, the relationship between the chairperson and the rapporteur is critical to the success of the committee's work. When the chairperson belongs to the majority and the rapporteur to the opposition, as is often the case with committees established under the drawing right, collaboration may be challenging.

The bureau of the PCI includes the chairperson, the rapporteur(s), vice-presidents and secretaries --all senators-- and functions as a forum for confidential deliberation. It defines the inquiry's strategic direction, settles internal disputes, and coordinates logistics. When a PCI is initiated under the drawing right, the bureau also serves as a conciliation body to facilitate cooperation between the majority and the opposition, particularly during the report drafting stage. Indeed, even though the opposition initiates the PCI, it cannot impose the final report, which must be adopted by a majority vote. This often requires the rapporteur to make concessions.

The administrative secretary - who is a member of the Parliament's civil service - operating under the joint authority of the chairperson and the rapporteur, plays a pivotal role in the organisation and execution of the committee's activities. This includes scheduling meetings, drafting questionnaires and reports, organising field visits and managing communication. The Head of Secretariat in particular acts as an intermediary between the chairperson and the rapporteur, a task that can be complex --especially when the two figures are reluctant to speak directly to one another. In such cases, the Head of Secretariat must serve as a go-between to maintain the functionality of the committee.

As for the methods and techniques employed by parliamentary committees of inquiry, hearings are naturally the most visible and widely used instrument. Most PCI hearings are held in public and are broadcast live. However, closed-door sessions may be organised when sensitive or confidential information is involved --for example, when ambassadors, judges, or the heads of independent authorities are called to testify. The decision to hold a hearing in public or in private is taken jointly by the chairperson and the bureau.

Written questionnaires constitute another essential investigative tool. These are prepared and sent by the rapporteur to individuals summoned by the committee and to relevant government departments in order to obtain precise facts and data. Particular attention must be paid to the confidentiality of certain information, which cannot be made public. Replies to these questionnaires are both legally and politically binding and must therefore be drafted with the utmost care.

In addition, the rapporteur has the authority to conduct on-site inspections and to request any document deemed useful to the inquiry. The mere possibility of such visits serves as a powerful incentive for cooperation, ensuring that written responses are accurate and that those interviewed contribute constructively to the hearings.

PCIs may also carry out field visits within France and, in some cases, abroad. These are especially relevant in inquiries relating to localised events, such as natural disasters, industrial accidents, or dysfunctions in the operation of public services. Nonetheless, the investigative powers of PCIs cannot be enforced beyond national borders.

Regarding the outcomes and follow-up of a PCI, the process culminates in the adoption of a final report. A few days before the closing session, the committee members are given access to the draft report. During the final meeting, the committee discusses possible amendments, after which a vote is held. As is always the case in parliamentary proceedings, the majority determines the outcome. When the majority has initiated the PCI, it can adopt the report unilaterally; however, even in such cases, efforts are usually made to obtain broader consensus in order to enhance the report's credibility and media impact.

A press conference is then held to present the report's findings, highlight any misconduct identified and announce the committee's recommendations. Typically, the final report includes between ten and twenty specific recommendations aimed at legislative or regulatory reform. In some cases, the report may lead to the introduction of a bill or the amendment of legislation already under discussion. Where potential criminal offences are uncovered, the PCI may refer the matter to the Ministry of Justice or directly to the public prosecutor, thereby triggering judicial proceedings.

4. Question-and-Answer session

During the question-and-answer session, participants raised questions about the investigative powers of committees of inquiry, how they interact with and differ from judicial proceedings (including rules regarding confidentiality and publicity), how judicial proceedings can be used to prevent a parliamentary inquiry from continuing its work, the personal rights of witnesses (especially when hearings are public and broadcast live), how these rights can be appealed if they are infringed, and the amount of human resources dedicated to PCIs within parliamentary administrations.

E. SESSION 2 - INVESTIGATIVE POWERS, METHODS AND TECHNIQUES

1. The resources available to parliamentary committees of inquiry and the methodology for gathering evidence, Mr Frank RAUE (Bundestag - Germany)

Drawing upon my experience with four parliamentary committees of inquiry, I would like to provide a brief overview of the resources available to such committees and the methodology they employ for gathering evidence.

There are three principal sources of evidence for parliamentary committees of inquiry: documents, witnesses and experts. Committees also possess the authority to carry out on-site inspections - for example, at facilities used to store nuclear waste -though such visits are not routine. In practice, the core investigative work centres on the collection and examination of documents, the questioning of witnesses, and the consultation of subject-matter experts.

Witness interviews are typically based on documents that the witness has authored, signed, or received. Accordingly, one of the very first steps taken by a newly established committee is to adopt a series of resolutions requesting the submission of documents from relevant government bodies. These resolutions are based on motions submitted by one or more parliamentary groups. Notably, if such a motion is supported by at least one-quarter of the committee's members, the committee is obliged to adopt it.

Motions to gather evidence are generally drafted by the staff of the parliamentary groups initiating the request. The committee's secretariat is rarely involved in this drafting process. Instead, the secretariat's main responsibilities at this stage are logistical: transmitting the adopted resolutions to the appropriate government departments, clarifying the preferred methods of document delivery, receiving and organising the submissions, and making the documents available to committee members.

Each government department implicated in the inquiry appoints a liaison to the committee. This person attends committee meetings and serves as the primary point of contact for the secretariat. When documents are submitted in paper format, the secretariat scans them and uploads them to the committee's digital drive, which is accessible to all members and parliamentary group staff. In recent years, however, most government submissions have been delivered electronically, typically via USB drives. The secretariat transfers these files to the committee's digital system. In the case of classified documents, special procedures apply. These materials are delivered to secure premises within the Bundestag, where they are copied onto designated laptops. Access to these laptops is strictly limited to those secure rooms, although they may be temporarily brought into the committee's meeting room when required for classified hearings.

Once the documents are made available, they are reviewed and analysed primarily by the parliamentary group staff. These materials often lead to the identification of new potential witnesses or the need for additional document requests. When a parliamentary group identifies a relevant witness through its analysis, it may seek a resolution to grant that person formal witness status. If the group holds at least one-quarter of the committee's seats, the resolution must be adopted. Otherwise, the group must obtain the support of other factions. Frequently, several groups identify the same key individuals, resulting in joint motions or proposals submitted by the chair on behalf of all parliamentary groups.

Through this iterative process, the committee progressively builds a comprehensive list of witnesses to be called in the course of its investigation.

However, the inclusion of a name on the list of potential witnesses does not automatically mean that the individual will be summoned. Instead, the senior staffers of the parliamentary groups meet regularly to deliberate on which witnesses should be heard and in what sequence. The outcome of these discussions is submitted to the spokespersons of the parliamentary groups, who typically endorse the proposal. It is then formally adopted at the subsequent committee meeting. Through this process, a witness hearing schedule gradually takes shape.

At the outset of the inquiry, this schedule is generally short-term in scope, covering only the upcoming one or two sessions. As the investigation advances, however, the schedule becomes more comprehensive and forward-looking. A common approach is to structure hearings by government department: witnesses from one department are questioned in sequence before moving on to another. Within each department, hearings often begin with officials at the lower levels of the hierarchy, followed by their direct superiors, then higher-ranking officials, culminating in the testimony of agency heads or cabinet members. These latter hearings are widely regarded as the inquiry's climax.

The secretariat is usually not involved in the strategic planning of witness sequencing, which remains the exclusive domain of the parliamentary groups. Once a consensus has been reached, typically conveyed by the chief staffer of the largest governing party, the secretariat is tasked with operationalising the decisions. This includes preparing the necessary meetings, organising logistics and implementing the committee's resolutions - for example, by sending formal invitations to witnesses and ensuring that the appropriate authorisations for their testimony are secured.

The weekly rhythm of these proceedings follows a well-established pattern, which is often as follows: on Tuesdays, the senior staffers of the parliamentary groups convene; on Wednesdays, the spokespersons meet; and on Thursdays, the committee itself assembles. Committee meetings are typically divided into two parts. First, a closed session is held to deliberate on procedural matters - such as the scheduling of witness hearings or the adoption of new resolutions to gather evidence. Then follows the public (though not broadcast) session, during which witnesses are formally questioned.

A standard session involves the examination of three to four witnesses, each interviewed individually. The process begins with the witness being invited to give an uninterrupted account from their own perspective. This is followed by questions from committee members, starting with the chair. The chair may be guided by a questionnaire prepared in advance by the secretariat. These questionnaires generally begin with basic queries about the witness's professional background, the mission of their department or unit, and their specific responsibilities. Additional questions address how the witness prepared for the hearing.

It is important to note that these questionnaires are not shared with witnesses in advance; they are strictly internal tools intended to help the chair and committee members structure their inquiries. The second half of the questionnaire typically delves into substantive matters, confronting the witness with documents they authored, signed or received, or with testimony previously provided by other witnesses.

After the chair concludes their line of questioning - which may or may not follow the full structure of the prepared questionnaire - the floor is opened to other committee members, who are free to pursue their own questions. The chair retains discretion over how many topics from the questionnaire are raised and how the hearing unfolds.

Witness hearings are structured into so-called rounds of questions, each typically lasting about one hour. Within each round, time is allocated to parliamentary groups in proportion to their size. If the chair belongs to a group of the governing coalition, the first slot after the chair's initial line of questioning is granted to the largest opposition group, followed by the governing coalition's partner group, then the second-largest opposition group, and so forth. This alternating sequence between majority and opposition parties ensures a balanced dynamic throughout the questioning.

Once the first round concludes, the chair will invite members to indicate whether further questions remain. In most cases, this leads to additional rounds - a second, third, and sometimes even a fourth or fifth - until all questions are exhausted. The questions posed by members are typically prepared in advance by the staff of their respective parliamentary groups. There is usually no coordination between groups regarding the substance or sequencing of their questions, and certainly no centrally coordinated interview strategy devised by the chair or the committee's secretariat.