SESSION 1

PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY

OF GOVERNMENTS'

EUROPEAN POLICY

I. INTRODUCTION

Mr Jean-François Rapin, Chairman

of the European affairs committee of the French Senate

I now propose that we begin our work and open the first session devoted to parliamentary scrutiny of European policy.

In June 1992, Pierre Bérégovoy's government escaped by just three votes the adoption of a motion of censure by the National Assembly. This motion had been tabled in opposition to the support he had given for the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy by the Council. This example serves to remind us that Parliament "controls the action of the Government", as the Constitution says, including the Government's European action. The positions it defends in Brussels or Luxembourg are binding on it before Parliament in Paris.

Once we have recalled this principle, the question is how to go about it. Because this control has certain specificities. There is often an asymmetry of information between the Parliament and the Government, which has access to draft legislation but is also directly involved in negotiations and therefore has a better understanding of the balance of power.

Similarly, this legislative activity takes place on a different agenda from the national agenda, and with different players. This is one of the reasons why Parliament has set up committees dedicated to European affairs, to better understand this different context.

Perhaps the main difficulty lies in the fact that the Council operates on the basis of negotiations, which involve a degree of confidentiality or "corridor discussions", and which lead to concessions being made if necessary, depending on the balance of power. Incidentally, the Council also has to negotiate with the European Parliament, often in the opaqueness of trilogues. How, in this context, can a government's responsibility be precisely identified?

All the parliaments of the European Union have had to confront these difficulties and it is interesting to note the diversity of responses, each with its own parliamentary traditions, its own law and its own political system.

I am delighted that this first session will enable us to study this diversity and I hope that we will be able to take a very practical look at the experiences of each national parliament: how much information does each national parliament really have from its government on the negotiations underway? For example, should ministers be heard behind closed doors so as not to disrupt the negotiations? Does the parliamentary negotiating mandate work well? We will look in particular at how the French system fits into this framework and whether improvements can be made.

II. NATIONAL CIRCUITS OF

PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF EUROPEAN UNION AFFAIRS: TOWARDS A CONVERGENCE OF THE

SCRUTINY MODELS?

Ms Elena Griglio, Parliamentary Senior Official of the

Italian Senate and Adjunct Professor at Luiss Guido Carli University in

Rome

1. Introduction: The national circuit of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs and its extra-territorial effects

I am extremely honoured and pleased to present my contribution to the challenging debate advanced by the Committee of EU affairs of the French Senate on the state of play of parliamentary scrutiny of EU matters.

I would like to express my respectful gratitude to President Larcher and to President Rapin for their kind invitation. I congratulate the Committee, including its Secretariat, on the high standard of this seminar and its excellent organisation.

The aim of my presentation is to analyse, from a comparative perspective, how national parliaments interpret and implement the scrutiny of EU affairs in the domestic interaction with their own governments.

This matter relies upon the most traditional form of democratic accountability that the European architecture has derived from national forms of government.

As a matter of fact, over the decades each national parliament has developed procedures and practices in order to hold the domestic executive accountable for the conduct of EU affairs. In some parliaments, including the legislatures of Nordic countries, the scrutiny of EU affairs has a long history and is solidly grounded in the interaction between the legislative and the executive branches312(*). Other assemblies, by contrast, can instead be considered latecomers to the consolidation of the scrutiny of EU affairs as a fully-fledged function313(*).

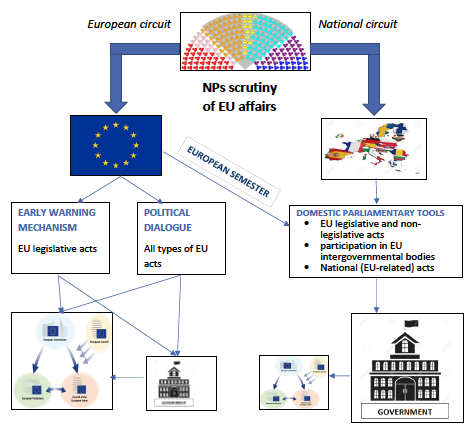

In the current Euro-national parliamentary system314(*), this set of national interactions covers only part of the procedures that enable national parliaments to participate in the EU decision-making process. As is shown in Figure 1, parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs unfolds via two different circuits315(*).

On the one hand, the European circuit, through the procedures of the Early Warning Mechanism (EWM) and the Political Dialogue, enables national parliaments to start a direct interaction with EU institutions on the adoption of EU legislative and non-legislative acts respectively316(*). The main aim of this interaction is to promote the participation of national representative assemblies from the very beginning of the decision-making process. Whereas the EU Commission is the principal recipient of parliamentary opinions and decisions, these may also indirectly influence the actions of the national executive.

On the other hand, the national circuit offers national parliaments the possibility to activate the oversight tools available at the domestic level in order to scrutinise executive action in all the spheres of activity related to participation in the EU, namely: the adoption of EU legislative and non-legislative acts, participation in intergovernmental bodies and the approval of national (EU-related) acts.

Figure 1 - European vs national circuits of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs

These procedures are capable of supporting the indirect involvement of domestic legislatures in all stages of the EU decision-making process.

Moreover, the effects of the national circuit of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs are clearly not confined to the Member States' level. By overseeing the actions of their own executive, national parliaments are able to produce `extra-territorial' effects, that is, to influence the activity of EU institutions and, concurrently, to strengthen the accountability of the EU architecture317(*).

While this is potentially an extremely powerful circuit, it is simultaneously very much dependent upon national legal and political, structural and transient factors318(*).

Based on these premises, this contribution aims to identify the factors at play at both the European and the national levels, which are influencing the institutional outcomes associated with the national circuit of scrutiny of EU affairs. After having explained the main organisational and procedural options and the primary models that shape national parliaments' approach to the scrutiny of EU affairs, the contribution focuses on the two rather diverging models of Italy and Finland. These case studies have been selected in order to demonstrate how parliaments with radically different approaches to the scrutiny of EU affairs have recently been experiencing a convergence, spurred by the latest trends in the EU, thus demonstrating how the current developments in EU integration favour a cross-fertilisation of national answers to common institutional needs, such as democratic oversight.

2. What impact can national parliaments' scrutiny of EU affairs produce? The European and national contextual factors

In order to assess the internal and extra-territorial effects associated with the national circuit of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs, two different sets of factors must be taken into consideration.

The first set of factors depends on the EU procedure in question and more specifically on the nature of the relevant European institution.

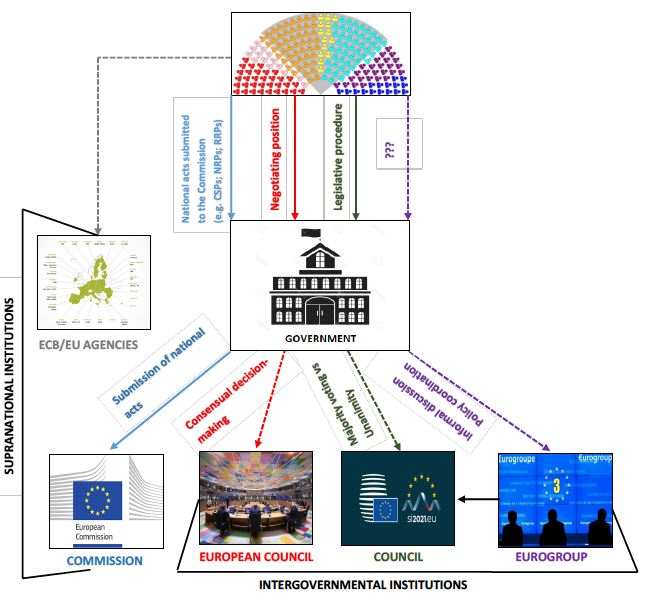

Figure 2 - The national circuit of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs and its interaction with EU institutions

Broadly speaking, the national circuit of parliamentary scrutiny is capable of producing its strongest extra-territorial effects when intergovernmental institutions are at stake. As a matter of fact, by controlling the positions adopted and votes expressed by their own executive, national parliaments are able to indirectly influence the decision-making process in both the European Council and the Council.

The nature of the influence exercised on intergovernmental institutions depends on a range of different procedural and institutional contextual features.

First, the type of impact produced is strongly influenced by the voting rules that support the European decision-making mechanisms. The influence of the national scrutiny circuit on EU inter-governmental institutions is strongest in the case of unanimous decision-making in the Council, but it clearly diminishes when majority voting is adopted. Its effect cannot be underestimated even in the case of consensual decision-making in the European Council319(*).

Moreover, among intergovernmental institutions, the activity of the Eurogroup can still be viewed as a sort of a gap in the accountability circuit. Due to the informality of its procedures, its lack of transparency and absence of real decision-making powers, it is extremely difficult for national parliaments to scrutinise the actions carried out by their own governments within this body320(*).

By contrast, the impact of the national scrutiny circuit on supranational institutions is much weaker.

In the case of the Commission, an indirect link connects this institution to the national scrutiny of EU affairs: this relates to the mechanisms that enable the participation of domestic legislatures in the procedures leading to the adoption of EU-related acts. Most of these mechanisms are rooted in the national rules and practices that structure the interaction between the legislative and the executive branches regarding EU policies. A topical example may be found in the procedures that involve parliaments in the adoption of the National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRRP). In certain cases, national parliaments' participation in such procedures is directly underpinned by EU legislation, as in the case of the adoption of the National Reform Programs and Stability or Convergence Programs under the European Semester321(*).

Other supranational institutions - including the European Central Bank and EU agencies - fall completely outside of the remit of the interaction between national parliaments and their domestic governments in the domain of EU affairs. Rather, national parliaments are able to initiate a direct interaction - not mediated by the executive - with these institutions, for instance by means of hearings or parliamentary debates.

Besides EU decision-making mechanisms, the other factor that influences the institutional outcomes of the national scrutiny circuit relates to parliaments' different capacities to oversee and bind their governments in the sphere of EU affairs. For example, only in some Member States (including Nordic countries following the `mandating' model - see infra) is the government formally bound to respect parliamentary instructions and parliaments have activated internal scrutiny mechanisms capable of encompassing any potential sphere of EU activity initiated by the executive.

The differences in the performance and effectiveness of the national scrutiny circuit at the domestic level depend on both legal and pre-legal factors.

In particular, five determinants seem to play a major role: first, the domestic institutional architecture, comprising the form of government, the executive/legislative interaction and the internal strength of parliament vis-à-vis the other branches322(*); second, the formal EU powers vested in the parliament by the Constitution, by the parliamentary Rules of Procedure, statutory legislation, internal conventions and practices, and their arrangements323(*); third, the political environment, resulting from party politics, from the executive-party relationship, and from the roles of the majority and the opposition in Parliament324(*); fourth, individual inclination to the scrutiny of EU affairs, visible via MPs' role orientations, motivations, interactions with voters and proximity to or distance from EU issues325(*); and fifth, the contextual factors, including the temporal coincidence with an emergency situation such as the Eurozone crisis, Brexit or the Covid-19 crisis326(*).

The combination of these legal and pre-legal determinants strongly influences the type of approach developed by each national parliament in overseeing the executive conduct of EU policies. However, regardless of domestic variations, several shared factors seem to allow the conception of the scrutiny of EU affairs as an autonomous and distinctive function.

3. How national parliaments shape the scrutiny of EU affairs: the main options available

As remarked in previous sections, parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs in the national circuit identifies a relational function that formally addresses the national government. At the same time, it also has extra-territorial reach, resulting in the indirect influence on EU institutions and in potential side effects produced in relation to other national parliaments.

While this function is autonomous, it is nevertheless interconnected with the other `traditional' parliamentary functions, including law-making, oversight and the setting of political directions. This link explains why the scrutiny of EU affairs unfolds through a wide range of domestic parliamentary tools and procedures, from the gathering of information or executive reporting to government statements and debates, and from hearings and inquiries to the questioning of or voting on resolutions and motions.

The following Figure 3 explains the different variables that shape the scrutiny of EU affairs as a parliamentary function.

|

Legal basis |

Constitutional basis |

Sub-constitutional rules and procedures |

Informal practices |

|

Object |

Document-based scrutiny (EU legislative and non-legislative proposals) |

Procedural scrutiny (including mandate-based) |

Scrutiny of national (EU-related) acts (e.g. CSPs; NRPs, RRPs) |

|

Timing |

Ex ante scrutiny · pre-legislative phase · before relevant intergovernmental meeting · before the adoption of the national (EU-related) act |

Ongoing scrutiny · in the legislative procedure, after the publication of the proposal · during the meeting · in the national process of adoption of an EU-related act |

Ex post scrutiny |

|

Scrutiny body |

EA (or equivalent) Committee |

EA & sectorial committees |

Plenary |

|

Parliamentary outcome |

Mandates/resolutions |

Transparency/debate |

Informal influence |

|

Party mode |

Consensual |

Traditional majority/opposition cleavage |

Strongly competitive |

Figure 3 - The main variables that influence national parliaments' scrutiny of EU affairs

The scrutiny of EU affairs may find its legal foundation in the Constitution itself, or in sub-constitutional sources of law - from statutory legislation to parliamentary rules and procedure -, usually integrated by informal practices.

Three different types of scrutiny can be activated at the national level: the document-based scrutiny327(*) gives parliaments the opportunity to examine and debate EU legislative and non-legislative proposals before their formal adoption by EU institutions; the procedural scrutiny (which includes mandate-based approaches328(*)) enables legislatures to oversee ex ante and also ex post the participation of their government in the EU decision-making process, including in Council and European Council meetings; and finally the scrutiny of national (EU-related) acts involves parliaments in the process of adoption of all the national decisions and acts which are grounded in the European governance, including the European Semester or the recovery governance.

Regardless of the type of scrutiny activated, from a timing perspective, three main options are offered to parliaments, enabling them to engage in ex ante scrutiny (which may affect the EU pre-legislative phase, the stage preceding the relevant intergovernmental meeting or the formation of the national act), in ongoing scrutiny (in the event that the parliament intervenes after the publication of a legislative proposal, during the intergovernmental meeting or during the national decision-making process instrumental to the adoption of a national, EU-related, act) or ex post scrutiny.

As for the internal organisation of this function, the scrutiny of EU affairs generally occurs within European affairs (or equivalent) Committees, in both European affairs and sectorial Committees or in the plenary329(*).

Focusing on the potential outcomes, parliamentary scrutiny may result in the adoption of formal positions and decisions, supported by voting on binding mandates or non-binding resolutions.

If binding mandates are able to ensure formal control over executive action at the EU level, up to the stipulation of explicit voting instructions, non-binding scrutiny mechanisms offer parliament the opportunity to exert a political influence on the government. This is particularly true in the case of upper Houses, whose independence from the continuum between the government and its parliamentary majority gives the opportunity to voice independent opinions and concerns. Before Brexit, the UK House of Lords' scrutiny of EU matters was a pivotal example of this type of `soft' influence on the executive330(*).

In many cases, however, scrutiny procedures may lack a formal outcome; in these cases, their primary purpose is to promote transparency and pluralistic debate on the executive conduct of EU affairs.

Finally, the party political style - whether this is consensual, taking the traditional form of a cleavage between majority and opposition, or strongly competitive - is another element that strongly influences the implementation of the scrutiny of EU matters at the parliamentary level.

National parliaments have combined these alternative options in rather original manners.

For the purpose of explaining these multiple combinations, literature has elaborated alternative classifications of national scrutiny models331(*). One of the most explicative classifications distinguishes five incremental categories of EU affairs scrutinisers, as follows: scrutiny laggards identify those parliaments with a lower level of involvement in EU affairs; public fora are the parliaments that tend to debate EU affairs mostly at the plenary level, both ex ante and ex post, therefore with greater transparency, but a lower level of specialisation and attention to technical issues; government watchdogs is the label attributed to those assemblies that scrutinise EU affairs both in committees and at the plenary level, but mainly in the ex post stage; policy shapers refers to the parliaments that tackle EU matters primarily in the ex ante phase, either in European affairs or in sectorial committees; and finally, experts deal with EU affairs in a highly professional and specialised manner, developing a strong ex ante expertise through committee work.

The following sections will analyse these categories diachronically.

4. Scrutiny models from a dynamic perspective: how national parliaments are reacting to major changes in the EU framework

The general categories identified for the purpose of explaining the original differences between the national scrutiny models must be viewed from a dynamic perspective in order to evaluate how they tend to adjust to ongoing changes in the contextual framework.

As a matter of fact, the last fifteen years have seen an intense cross-fertilisation of national experiences, favoured by several ongoing trends332(*). These comprise the strengthening of the dialogue between representative assemblies, thanks to the initiation of the Early Warning Mechanism and political dialogue and to the intensification in inter-parliamentary cooperation as well as the determination, in response to the Eurozone crisis, of the new economic governance, which reinforces the European role of national parliaments in the European Semester. Moreover, the crises (Eurozone, Brexit, migration and Covid-19) which the EU has experienced over the last two decades have contributed to the implementation of political and institutional adjustments at the Member States' level, which has often resulted in the rapprochement of national models.

a) Comparing two alternative scrutiny models: the Finnish and Italian cases

The rapprochement of national scrutiny models is best demonstrated by the experiences of Italy and Finland. I have selected these benchmarks by reference to the original differences between the two models as well as to the transformation that they have recently undergone.

Historically, the Finnish and Italian Parliaments have represented the prototypes of two diverging means of approaching EU matters, rooted in models and traditions of scrutiny which, from a comparative viewpoint, can be considered to be the two opposite poles of the European framework.

However, in the last fifteen years, these two models have experienced a sort of convergence based on the hybridisation of their traditional features through the introduction of tools and practices derived from the other prototype.

A synthesis of the original differences between the two parliamentary experiences is offered in Figure 4.

|

FINLAND |

ITALY |

|

|

Legal base |

Strong constitutional base (Section 47, 96, 97 Const.) |

Sub-constitutional legal base (L. 11/2005, replaced by L. 234/2012; Parliamentary Rules of Procedure) |

|

Type of scrutiny |

Strong document and mandate-based scrutiny · Unlimited access to information · Government reports · Committee statements · Rather sporadic debates in plenary sessions |

Before Lisbon: weak document-based model (scrutiny reserves rarely used) After Lisbon: · the EWM intensifies the document-based scrutiny · introduction of procedural scrutiny in the plenary, addressing the European Council + strengthening of the scrutiny of national (EU-related) acts |

|

Timing |

Ex ante (from the very early stages of policy formulation) Ongoing (during legislative negotiations/meetings) Ex post (after the meetings) |

Document scrutiny: mostly ongoing (after publication of the legislative proposal), only rarely in the pre-legislative stage Procedural scrutiny: ex ante Scrutiny of national (EU-related) acts: ex ante |

|

Scrutiny body |

Centrality of committees: strong role of the Grand Committee, complemented by the Foreign Affairs and sectorial committees Limited involvement of the plenary, mostly for debates focused on `high politics' (not for decisions) |

Document scrutiny: occasional involvement of standing committees (depending on the political salience of the issue) Procedural scrutiny: systematic involvement of the plenary (European Council) Scrutiny of national (EU-related) acts: both committee and plenary stage |

|

Parliamentary outcome |

Committee statements with a binding mandate |

Committee or Plenary resolutions (non-binding or moderately binding) |

|

Party mode |

Consensual style («to speak with one voice on all levels of decision-shaping in Brussels») Active role of the opposition in committee work |

EU affairs tend to follow the traditional majority/opposition divide Relatively few partisan ideological debates |

Figure 4 - Comparison between the Finnish and Italian scrutiny of EU affairs

On the one hand, Finland - a latecomer to EU integration - offers an example of a strong scrutiniser of EU affairs333(*). This function is grounded in the Constitution and, since Finland's accession to the European Communities, it has been supported by a solid document and mandate-based scrutiny. Four main strengths explain the robustness of the Eduskunta's involvement in EU policy-making334(*).

The first strength can be identified in the constitutional provisions that formally recognise the role of the parliament and its committees in the scrutiny of EU affairs, regulating their participation in the national preparation of European Union matters (section 96) and their information rights (section 97).

After its accession to the European Community, the Eduskunta decided not to establish a special European affairs Committee, but rather relied upon a pre-existing committee, the Grand Committee, as the pivotal body responsible for coordinating the position of the parliament on EU matters. This choice has been formally adopted in the Constitution.

The second strength of the Finnish scrutiny model relates to the unlimited access to information in possession of public authorities which parliament and its committees enjoy in the consideration of all relevant matters, including EU affairs.

The reduction in information asymmetries represents a fundamental tool for the purpose of promoting government accountability in a sphere of action strongly permeated by executive dominance.

Parliament's information rights regarding EU matters are specifically mentioned in and regulated by sections 96 and 97 of the Constitution. These prerogatives are, however, complemented by the general right - recognised by sections 44335(*) and 46 Const. - to receive reports from the cabinet, as well as the government's annual report on its activities.

These mechanisms enable MPs to be informed in a timely manner about the conduct of EU matters by executive bodies.

The effectiveness and continuity of the informative exchange between government and parliament is a prerequisite for determining the timing of parliamentary scrutiny. Indeed, its capacity to cover the entire decision-making process constitutes another strength. The Eduskunta intervenes from the very early stages of policy formulation, which offers MPs the opportunity to identify, from the outset, potentially controversial issues and to tell the government how to address them at the European level. The dialogue between parliament and government then follows all the intergovernmental negotiations and the whole legislative process.

Ministerial hearings take place in the Grand Committee both before the meeting of the Council, when required, and immediately afterwards. The regularity of this exchange of views and opinions has significantly improved the dialogue between the Eduskunta and the Government, strengthening policy coordination, spurring executive responsibility on the management of EU matters and reinforcing parliament's capacity to influence decision-making.

What makes the Finnish scrutiny of EU affairs so incredibly effective is, however, the role of its committees. This scrutinising function is undertaken by the Grand Committee, complemented by the Foreign Affairs and by the other specialised standing committees336(*).

The latter monitor European matters and report to the Grand Committee by submitting their guidelines. Based on this preliminary work and on the information received by the government, the Grand Committee may draft a statement which becomes politically binding on the executive.

In the original Finnish scrutiny model, the bulk of EU affairs scrutiny was therefore vested in the committees, while public debates in the plenary played a marginal role. Committee work offered the opportunity to cooperate in an informal manner, promoting a fruitful bipartisan dialogue, as well as the active participation of the opposition in the formulation of national EU policy.

The predominant nature of the Eduskunta as a `working parliament' therefore also explains the consensual approach traditionally taken to shaping the handling of EU matters337(*). Pragmatism, inter-party cooperation, lack of partisan divisions and ideological debates were the dominant attitudes which featured in the national coordination of EU matters. Their main aim was to facilitate consensus-building, so that Finland could `speak with one voice on all levels of decision-shaping in Brussels'338(*) (on the latest evolutions of this model, see 4.2).

On the other hand, the Italian case provides an insight into the experience of a country which, despite being one of the founders of the European Communities, has always lacked a tradition in the scrutiny of EU affairs comparable to the standards set by Northern Europe339(*). Legislation has been the dominant answer to the management of EU matters and only in the last fifteen years, due to the concurrence of both European and national factors, has Italy also been able to carve out a role for parliament in the scrutiny of EU matters340(*).

The historical weakness of the Italian legislature in this field pairs with the absence of a constitutional reference to parliamentary scrutiny of EU matters341(*). Statutory laws and parliamentary rules of procedure have partially attempted to fill this gap, but in the pre-Lisbon framework, parliamentary scrutiny continued to follow a weak document-based model, involving only an extremely modest use of the tool of parliamentary reserves.

The entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty launched new forms of institutional engagement of the Italian Parliament in the consideration of European issues and in the participation in EU decision-making342(*).

From a legal point of view, the need to comply with the revised EU institutional framework has primarily been satisfied through the approval of Law no. 234/2012, `General rules on Italy's participation in the formation and implementation of legislation and policies of the European Union'343(*). This was followed up by the two Houses mostly through `internal' acts and practices344(*), which were only translated into formal amendments to the rules of procedure in the upper House, the Senate.

The Italian Parliament in the post-Lisbon era has experienced the consolidation of both the document-based and the procedural scrutiny, which have, however, - at least until the end of 2021 - followed procedures and mechanisms which are quite different from those of the Nordic model.

The intensification of the document-based scrutiny of EU affairs can be viewed as one main adaptation to the Early Warning Mechanism. In both Houses, the scrutiny rests on the role of sectorial standing committees as well as of the European affairs Committee. Its timing, which commences upon the publication of the legislative proposal, tends to follow the legislative negotiations in Brussels. Cases of pre-legislative scrutiny dissociated from the EWM are extremely rare.

The document-based scrutiny is concluded by the adoption of a committee resolution, which is submitted to the consideration of the government. From a legal perspective, these acts are not binding on the executive. It is therefore extremely difficult to trace their influence on the executive's management of EU affairs.

At the same time, Law no. 234/2012 has promoted the structural engagement of the plenaries of both Houses in the preliminary scrutiny of government action before the meetings of the European Council. The procedure begins with the President of the Council of Ministers or delegated Minister making a statement in both Houses outlining the position to be held at the European Council meeting; the statement is followed by a debate, and concluded by the adoption of one or more resolutions. These resolutions usually include broad political directions to the executive, which are agreed between the government and its parliamentary majority.

The combination of these mechanisms confirms that Italy's post-Lisbon parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs has evolved into a hybrid model rooted in the role of the plenary for the procedural scrutiny and in committee work for the document-based scrutiny. The outcome of parliamentary involvement (until the latest legislative innovations - see 4.2) has been the adoption of resolutions which do not bind the government from a legal viewpoint, but which must be framed and interpreted in the context of the executive-legislative political interaction.

From a political perspective, Italy has traditionally been characterised by a clearly pro-European orientation both in the realm of public opinion and in the political system345(*). Notwithstanding the rise of Eurosceptic positions within some centre-right parties346(*), Parliament has continued to record a significantly low level of involvement in, and a reduced rate of politicisation of, European issues347(*).

Debates and decisions on topical EU issues tend to follow the cleavage between the majority and opposition, and give rise to relatively few partisan ideological debates348(*), as EU matters in themselves are rarely perceived to be divisive topics.

b) Current adaptations in the Finnish and Italian scrutiny models: towards a convergence?

The major changes to the governance of the European Union brought about by the Eurozone349(*) and Covid-19 crises350(*) have strongly influenced the scrutiny practices and mechanisms both in the Finnish and in the Italian Parliaments.

On the one hand, the Finnish approach to the scrutiny of European affairs has started experiencing a major transformation in the context of the Eurozone crisis. Several factors spurred this change, including: the spread of anti-European sentiments among voters; the overwhelming success of the Eurosceptic Party Finns in the 2011 parliamentary elections; the transition to a coalition government; and the hardening of the Finnish policy on EU membership. The different political climate has deeply influenced the work of the Eduskunta, breaking with the traditional consensual style and favouring the appearance of forms of opposition. The impact of these trends on parliamentary scrutiny procedures has led to a shift in the setting for the debate from committee sessions to plenary meetings, where sharp divisions and criticism of the government's actions have emerged351(*).

Committee decisions, traditionally adopted in a consensual manner, have started indicating a dependence on majority voting procedures. The opposition has begun to make extensive use of dissenting opinions alongside the adoption of the statements of the Grand Committee.

The politicisation of European issues experienced by the Finnish Eduskunta in the context of the Eurozone crisis has further developed during the Covid-19 crisis. The procedures activated by the Eduskunta in connection with the various instruments of the stimulus package indicate a general shift in the debate from the committees' informal working atmosphere to the more open and competitive environment of the plenary sessions, where the confrontation between the political forces often becomes tough and hard fought352(*).

The Constitutional Law Committee itself requested, as a guarantee, a plenary vote by a two-thirds353(*) majority for the approval of the three main decisions concerning the stimulus package: the Own Resources Decision354(*), the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027355(*) and the Recovery and Resilience Instrument356(*).

This procedural framework has not prevented minority forces from assembling a strong opposition to these decisions, motivated by a radical critique of the government's action357(*). In the case of the MFF and the Recovery Mechanism, the opposition went as far as activating forms of parliamentary obstructionism that generated significant concern at the European level too358(*). Moreover, minority parties continued to make extensive use of dissenting opinions and resolutions in both the plenary and the committees359(*).

Overall, the pandemic crisis has continued and accentuated the paradigm shift which, since the Eurozone crisis, has gradually overcome the traditional consensual, working parliament style which previously characterised the Eduskunta's approach to EU affairs.

On the other hand, the transformations experienced by the Italian parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs in the context of the Eurozone and Covid-19 crises seem to follow a direction complementary to that of the Eduskunta.

Besides the instances of document-based and procedural scrutiny developed in both Houses after the Lisbon Treaty, new practices of parliamentary involvement in the scrutiny of national (EU-related) acts have started to spread in the novel architecture of the European Semester and of the recovery governance.

The European Semester has encouraged the participation of the Italian Parliament in the adoption of the National Reform and Stability Programs, which are examined within the framework of the Economic and Financial Document, which is the general macro-economic plan that sets the priorities and guidelines for the next cycle of public finance. The scrutiny procedures impose a relevant fact-finding and reporting role on the budget committees of the two Houses, while also attributing a strong role to the plenary debate, which is concluded with the approval of a majority resolution formally authorising the government to submit the National Reform and Stability Programs to the EU Commission.

A not too dissimilar procedure has supported the Italian Parliament's participation in the adoption of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan. Even if the European stimulus package does not include any reference to the role of national parliaments360(*), the Italian Parliament has been one of the most proactive in scrutinising executive activity at different stages of the drafting and adoption of the NRRP. The two Italian Houses are among the few assemblies involved in three subsequent stages: in the ex post scrutiny of the Guidelines for drafting the NRRP361(*); in the ex post scrutiny of the Draft Plan362(*); and in the ex ante scrutiny of the Final Plan. The first two stages have involved both the committee and the plenary level363(*).

As for the implementation stage, two statutory provisions have formally recognised the oversight role of parliament in monitoring the execution of NRRP projects and the maintenance of the timeline agreed with EU institutions. This role is exclusively undertaken by standing committees, whose informative prerogatives have been strengthened in order to support the formulation of observations and evaluations that may improve the implementation of the NRRP364(*). Moreover, standing committees are involved in the scrutiny of the six-monthly reports on the NRRP implementation submitted by the government: based on intense fact-finding365(*), the procedure may be completed with the adoption of resolutions addressing political directions to the government on the weaknesses detected in the implementation stage.

Practices started under the European Semester and the recovery governance have therefore confirmed a new place for the parliament in the scrutiny of EU-related (national) acts, with a steering role attributed to the committees.

Meanwhile, the European Law 2019-2020 (Law 23 December 2021, n. 38) has strongly reinforced the Italian Parliament's procedural scrutiny mechanisms, formally introducing some tools typical of the Nordic model.

The new framework legislation on participation in the EU standardises parliament's procedural scrutiny before Council meetings rather than it being sporadic. Moreover, the legislation extends this mechanism to meetings of the Eurogroup. The procedure requires the government to present a statement before relevant committees, which can then adopt resolutions confirming the principles and guidelines on the position to be supported in the preparatory stage that precedes the adoption of EU acts366(*).

Another relevant novelty is that the acts adopted by parliament, addressing political directions to the government on EU matters, are considered binding on the executive367(*).

These amendments are clearly introducing a strong model for the scrutiny of EU affairs in the Italian Parliament, which is shaped on the experience of the Nordic model. It can therefore be argued that the economic and health crises have accelerated and intensified the Europeanisation of the Italian parliamentary procedures.

At the same time, both crises have resulted in the management of EU politics being increasingly politicised368(*): they have been among the factors fuelling the resignation of the interim government and the shift to a new cabinet supported by large coalitions and inflated with technocratic elements369(*). However, in both cases, the government turnover has marked the return to low rates of politicisation of EU affairs370(*), aligned according to the cleavage between majority and opposition.

|

Traditional features |

Latest adaptations |

Effects on the model |

|

|

FINLAND |

Solid constitutional basis Strong document and mandate -based scrutiny Ex ante, ongoing, ex post scrutiny Centrality of Committee work Consensual approach to EU matters |

Politicisation of EU affairs spurred by the growing salience of the Euro crisis and of the stimulus measures More voting instead of unanimous committee decisions Dissenting opinions of the opposition to committee statements and minutes |

The Eduskunta, from working to talking parliament · Increased role of the plenary · Filibustering in the plenary |

|

ITALY |

Relevant changes in the scrutiny of EU affairs after Lisbon · Procedural scrutiny of the European Council in the plenary · Role of the committees in the document-based scrutiny spurred by the EWM/political dialogue · Formal regulation of the procedural scrutiny: committee or plenary resolutions (non-binding or moderately binding) |

Attempt to further strenghten parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs by adjusting to the Nordic scrutiny model EU 2019-2020 Act · Systematic procedural scrutiny of the Council, extended to the Eurogroup, at the committee level · Binding effects of parliamentary resolution on EU matters |

The Italian Parliament turning into a working parliament · Increasing fact-finding role of the committees in the Recovery governance · Increasing role of standing committees in the procedural scrutiny |

Figure 5 - Latest adaptations in the Finnish and Italian scrutiny models

5. Conclusions

The national circuit of parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs is a rather powerful tool for promoting the democratic accountability of EU decisions.

Its main strength consists of the extreme richness and flexibility of the oversight tools and procedures that national parliaments can activate in order to control their government's conduct of EU matters. In extreme circumstances, these can eventually lead to the removal of confidence from the interim cabinet.

The traditional weaknesses of this scrutiny circuit relate instead to the limited scope of the national oversight tools and procedures - which, due to their domestic nature are not always able to produce an impact on the EU decision-making process, - and to the intense divergence between national scrutiny models.

As to the latter aspect, in fact, relevant changes can be discerned in the last fifteen years. The novelties introduced with the Lisbon Treaty and, indirectly, with the new governance designed in response to the Eurozone and the Covid-19 crises, have promoted an intense Europeanisation of national parliaments and their interparliamentary dialogue. At the domestic level, these trends have favoured the consolidation of the scrutiny of EU matters as a proper parliamentary function, enriching the tools and procedures available to national parliaments. Lately, this has resulted in a cross-fertilisation of national scrutiny models.

The rapprochement of the scrutiny models is spurred by different factors.

On the one hand, Finland's case, which this contribution has examined, offers an example of the hybridisation of the Nordic scrutiny model fostered by political and domestic factors, namely the increased political salience gained by the scrutiny of EU affairs in `frugal' countries in the context of the Eurozone/Covid-19 crises. The increasing politicisation of EU matters in the Finnish Eduskunta has favoured the consolidation of an emerging role for the plenary as a `debating forum', eschewing the traditional role of committees as the main EU scrutinisers.

On the other hand, Italy's case is emblematic of ongoing adjustments in the parliamentary scrutiny model spurred by domestic adaptations to external trends, namely the Europeanisation of a national parliament traditionally identified as a `scrutiny laggard' in response to the Lisbon Treaty, to the European Semester and to the Recovery architecture. The will to reinforce the role of parliament in the scrutiny of EU matters has promoted the transplantation into the Italian system of features typical of a `working parliament', derived from the Nordic scrutiny model. These comprise the pivotal role attributed to committee work in the field of EU affairs and the binding nature of the resolutions voted by parliament regarding the executive.

The cross-fertilisation of national tools and procedures in the scrutiny of EU matters can be evaluated in a positive manner, as a trend which will inevitably strengthen the domestic oversight machinery available to national parliaments and potentially result in a reparliamentarisation of EU affairs at both national and European level371(*).

At the same time, however, there are still other weaknesses that need to be addressed.

One relates to the democratic accountability of emerging EU bodies, such as the Eurogroup and the Euro Summit, which tend to escape the traditional national scrutiny procedures. In this domain, the novelty introduced in Italy, whereby parliamentary committees are now asked to extend the procedural scrutiny of executive action to the meetings of the Eurogroup, will be a rather significant experience to monitor.

The other relevant weakness remains in the limited effects of national parliaments' scrutiny of supranational institutions and also of intergovernmental institutions when majority voting is at stake. To cover these spheres of decision-making, it is clear that the simple `summation' of national scrutiny mechanisms is insufficient alone. Rather, we need transformative mechanisms capable of promoting the consolidation of joint parliamentary scrutiny at the UE level, such as those rooted in inter-parliamentary cooperation372(*).

* 312 E. Damgaard and H. Jensen, `Europeanisation of Executive-Legislative Relations: Nordic Perspectives', in Journal of Legislative Studies, n. 11, 2005, p. 394 ff; F. Laursen, `The role of national parliamentary committees in European scrutiny: Reflections based on the Danish case', ivi, p. 412 ff. D. Finke and M. Melzer, Parliamentary Scrutiny of EU Law Proposals in Denmark: Why do Governments Request a Negotiation Mandate?, Vienna, Institute for Advanced Studies, 2012, p. 30.

* 313 A. Maurer and W. Wessels (eds), National Parliaments on Their Ways to Europe: Losers or Latecomers?, Baden-Baden, Nomos, 2001. C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg and J. Smith (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

* 314 On the conceptualisation of the `Euro-national system', see A. Manzella and N. Lupo (eds), Il sistema parlamentare euro-nazionale. Lezioni, Torino, Giappichelli, 2014. See also C. Fasone and N. Lupo, `Conclusion. Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Framework of a Euro-national Parliamentary System', in N. Lupo and C. Fasone (eds), Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2016, p. 345 ff; N. Lupo, `In the Shadow of the Treaties: National Parliaments and Their Evolving Role in European Integration', in Politique Europe'enne, n. 59, 2018, p. 196 ff.

* 315 N. Lupo and G. Piccirilli, `Introduction: The Italian Parliament and the New Role of National Parliaments in the European Union', in Id (eds), The Italian Parliament in the European Union, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2020, p. 1 ff.

* 316 A. Jonsson Cornell and M. Goldoni (eds.), National and Regional Parliaments in the EU-Legislative Procedure Post Lisbon, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2017. D. Janèiæ, `The Barroso Initiative: Window Dressing or Democracy Boost?', in Utrecht Law Review, n. 8-1, 2012, p. 84. P. Casalena, N. Lupo and C. Fasone, `Commentary on Protocol No 1 annexed to the Treaty of Lisbon (On the role of National Parliaments)', in H.J. Blanke e S. Mangiameli (eds), The Treaty on European Union, Berlin, Springer, 2013, p. 1529 ff; O. Rozenberg, The role of National Parliaments in the EU after Lisbon, Brussels, European Parliament, 2017.

* 317 See E. Griglio, Parliamentary oversight of the executives. Tools and procedures in Europe, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2020, p. 191 ff. The extra-territorial effects associated to the national circuits of scrutiny of EU affairs are strongly influenced by the `two-level games' started on EU matters by domestic politics who can `tie the hands of diplomats', see R. Phare, `Endogenous domestic institutions in two-level games and parliamentary oversight of the European Union', in The Journal of Conflict Resolution, n. 41, 1997, p. 148 ff.

* 318 P. Kiiver, The National Parliaments in the European Union: A Critical View on EU Constitution-building, The Hague, Kluwer Law, 2006, p. 48.

* 319 E. Griglio, `Divided accountability of the Council and the European Council. The challenge of collective parliamentary oversight', in D. Fromage e A. Herranz Surralles (eds), Executive-Legislative (Im)Balance in the European Union, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2020, p. 51 ff.

* 320 C. Dias, K. Hagelstam and W. Lehofer, The role (and accountability) of the President of the Eurogroup, European Parliament - EGOV Briefing, 16 June 2021. P. Craig, `The Eurogroup, power and accountability', in European Law Journal, n. 22-3/4, 2017, p. 234 ff. J. Abels, `Power behind the curtain: the Eurogroup's role in the crisis and the value of informality in economic governance', in European Politics and Society, 2018, p. 1 ff.

* 321 E. Griglio and N. Lupo, `Parliamentary democracy and the Eurozone crisis', in Law and Economics Yearly Review II, 1, 2012, p. 313 ss. C. Hefftler and W. Wessels, `The Democratic Legitimacy of the EU's Economic Governance and National Parliaments', in IAI Working Papers, n. 13, 2013. M. Dawson, `The Legal and Political Accountability Structure of `Post-crisis' EU Economic Governance', in Journal of Common Market Studies, n. 53-5, 2015, p. 976 ff. T. Van den Brink, `National Parliaments and EU Economic Governance. In Search of New Ways to Enhance Democratic Legitimacy', in F.A.N.J. Goudappel and E.M.H. Hirsch Ballin (eds), Democracy and Rule of Law in the European Union, T.M.C. Asser Press, 2016, p. 15 ff. A. Cygan, `Legal Implications of Economic Governance for National Parliaments', in Parliamentary Affairs, n. 70-4, 2017, p. 710 ff.

* 322 T. Raunio, `Holding Governments Accountable in European Affairs: Explaining Cross-National Variation', in The Journal of Legislative Studies, n. 11, 2005, p. 319 ff.; A. Cygan, Accountability, Parliamentarism and Transparency in the EU: The Role of National Parliaments, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2013; D. Fromage, Les Parlements dans l'Union Européenne après le Traité de Lisbonne. La Participation des Parlements allemands, britanniques, espagnols, français et italiens, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2015; L. Besselink, `The Place of National Parliaments within the European Constitutional Order', in N. Lupo and C. Fasone (eds), Interparliamentary Cooperation in the Composite European Constitution, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2016, p. 23 ff.

* 323 K. Auel, O. Rozenberg and A. Tacea, `Fighting Back? And, if so, How? Measuring Parliamentary Strength and Activity in EU Affairs' in C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg and J. Smith (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union (London, Palgrave, 2015) p. 60 ff. Id., `To Scrutinise or Not to Scrutinise? Explaining Variation in EU-Related Activities in National Parliaments', in West European Politics, n. 38:2, 2015, p. 282 ff. K. Gattermann, A.L. Högenauer, and A. Huff, `National Parliaments after Lisbon: Towards Mainstreaming of EU Affairs?', in OPAL Online Paper, no. 13, 2013.

* 324 T. Winzen, `National Parliamentary Control of European Union Affairs: A Cross-national and Longitudinal Comparison', in West European Politics, n. 35, 2012, p. 657 ff. J. Karlas, `National Parliamentary Control of EU Affairs: Institutional Design after Enlargement', ivi, p. 1095 ff. K. Auel, `Democratic Accountability and National Parliaments: Redefining the Impact of Parliamentary Scrutiny in EU Affairs', in European Law Journal, n. 13, 2007, p. 487 ff. D. Finke and A. Herbel, `Coalition Politics and Parliamentary Oversight in the European Union', in Government and Opposition, n. 53, 2018, p. 388 ff. A. Strelkov, `Who Controls National EU Scrutiny? Party Groups, Committees and Administrations', in West European Politics, n. 38:2, 2015, p. 355 ff.

* 325 K. Goetz and J. Meyer-Sahling, `The Europeanization of National Political Systems: Parliaments and Executives', in European Governance, n. 3: 2, 2008. B. Wessels, `Roles and Orientations of Members of Parliament in the EU Context: Congruence or Difference? Europeanisation or not?, in The Journal of Legislative Studies, n. 11, 2005, p. 446 ff. O. Rozenberg, `The Emotional Europeanisation of National Parliaments: Roles Played by EU Committee Chairs at the Commons and at the French National Assembly', OPAL Online Paper Series, 2012. K. Auel and T. Christiansen, `After Lisbon: National Parliaments in the European Union, in West European Politics, n. 38:2, 2015, p. 261 ff.

* 326 K. Auel and O. Hoïng, National Parliaments and the Eurozone Crisis: Taking Ownership in Difficult Times?, in West European Politics, n. 38:2, 2015, p. 375 ff. D. Jançic (ed), National Parliaments after the Lisbon Treaty and the Euro Crisis: Resilience or Resignation?, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017. B. Crum, `Parliamentary accountability in multilevel governance: what role for parliaments in post-crisis EU economic governance?', in Journal of European Public Policy, n. 25, 2017, p. 268 ff. T. Christiansen and D. Fromage (eds.), Brexit and Democracy. The Role of Parliaments in the UK and in the European Union, London, Palgrave MacMillan, 2019. C. Deubner, The Difficult Role of Parliaments in the Reformed Governance of the European Economic and Monetary Union, Brussels, Foundation for European Progressive Studies No. 19, 2013.

* 327 On the difference between document-based and mandate-based scrutiny models, see COSAC, Third Bi-annual Report `Developments in European Union Procedures and Practices Relevant to Parliamentary Scrutiny', Brussels, COSAC Secretariat, 17-18 May 2005 and Id., Eight Bi-annual Report `Developments in European Union Procedures and Practices Relevant to Parliamentary Scrutiny', Brussels, COSAC Secretariat, 14-15 October 2007.

* 328 On the adoption of negotiating mandates to the government, along the lines of the procedure introduced in 1973 by the Danish Parliament, the Folketing, and subsequently adopted by other assemblies, including the Swedish Riksdag and the Finnish Eduskunta, see F. Laursen, `The role of national parliamentary committees in European scrutiny: Reflections based on the Danish case', in The Journal of Legislative Studies, no. 11, 2005, p. 412 ff. P. Kiiver, The National Parliaments in the European Union: A Critical View on EU Constitution-building, The Hague, Kluwer Law, 2006, p. 48. D. Finke e M. Melzer, Parliamentary Scrutiny of EU Law Proposals in Denmark: Why do Governments Request a Negotiation Mandate?, Vienna, Institute for Advanced Studies, 2012, p. 30.

* 329 A.L. Högenauer, `The mainstreaming of EU affairs: a challenge for parliamentary administrations', in The Journal of Legislative Studies, no. 27:4, 2021, p. 535 ff.

* 330 See L Boswell, `Effective House of Lords scrutiny of the European Union', in R. Fox et al, Measured or Makeshift? Parliamentary scrutiny of the European Union, London, Hansard Society, 2013, p. 23 ff.

* 331 W. Wessels and O. Rozenberg (eds), Democratic control in the Member States of the European Council and the Euro Zone Summits, Brussels, EU Parliament - Directorate General for internal policies, 2013. O. Rozenberg and C. Hefftler, `Introduction' in C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg and J. Smith (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union, London, Palgrave, 2015, p. 1 ff. K. Auel, O. Rozenberg and A. Tacea, `Fighting Back? And, if so, How? Measuring Parliamentary Strength and Activity in EU Affairs' in C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg and J. Smith (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union, London, Palgrave, 2015, p. 60 ff.

* 332 For an overview of the factors identified by political science or public administration studies in order to explain the process of `Europeanisation' of national parliaments, see K. Gattermann, A.L. Högenauer and A. Huff, `Research Note: Studying a New Phase of Europeanisation of National Parliaments', IN European Political Science, N. 15:1, 2016, p. 89 ff, spec. Figure 1.

* 333 T. Raunio, The Finnish Eduskunta and the European Union: The Strengths and Weaknesses of a Mandating System, in C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg and J. Smith (eds), The Palgrave Handbook, cit., p. 406 ff.

* 334 K. Strøm, `Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracy', in European Journal of Political Research, n. 37, 2000. T. Raunio and T. Tiilikainen, Finland in the European Union, Frank Cass, 2003.

* 335 Section 44 regulates the government's duty to present a statement or report to the parliament on a matter relating to the governance of the country or its international relations: at the conclusion of the consideration of a statement, a vote of confidence shall be taken; by contrast, no decision on confidence shall be advanced during the debate of a report.

* 336 M. Boedeker and P. Uusikyla·, Interaction Between The Government And Parliament In Scrutiny Of EU Decision-Making; Finnish Experiences And General Problems, Eduskunta, 1999.

* 337 D. Arter, Politics and Policy-Making in Finland: A Study of a Small Democracy in a West European Outpost, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 1987; A. Hyvarinen and T. Raunio, `Who Decides What EU Issues Ministers Talk About? Explaining Governmental EU Policy Coordination in Finland', in Journal of Common Market Studies, n. 52:5, 2014, p. 1019 ff.

* 338 A. Stubb, Finland: An integrationist Member State, Boulder, Lnne Rienner, 2001. See also J. Jokela, Europeanization and Foreign Policy: State Identity in Finland and Britain, Abingdon, Routledge, 2011.

* 339 K Auel, O Rozenberg and A Thomas, `Lost in Transaction? Parliamentary Reserves in EU bargains' (2012) 10 OPAL Online Paper Series. A Buzogány, `Learning from the best? Interparliamentary networks and the parliamentary scrutiny of the EU decision-making' in B Crum and E Fossum (eds), Practices of interparliamentary coordination in international politics, Colchester, ECPR Press, 2013, p. 17 ff.

* 340 V. N. Lupo and G. Piccirilli, `Conclusion: 'Silent' Constitutional Transformations: The Italian Way of Adapting to the European Union', in Id (ed.), The Italian Parliament, cit., p. 317 ff. and G. Rizzoni, `The Function of Scrutiny and Political Direction of the Government, Between Foreign Affairs and European Affairs', ivi, p. 87 ff.

* 341 Ex multis, see M. Cartabia and L. Chieffi, `Art. 11' in Commentario alla Costituzione, Torino, UTET, 2006; P. Bilancia, The dynamics of the EU integration and the impact on the national Constitutional Law, Milano, Giuffrè, 2012, p. 86 ff.

* 342 See A. Esposito, `European Affairs within the Chamber of Deputies' and D. Capuano, `European Affairs within the Senate of the Republic', in N. Lupo and G. Piccirilli (eds.), The Italian Parliament, cit.

* 343 See, ex multis, N. Lupo, `L'adeguamento del sistema istituzionale italiano al trattato di Lisbona. Osservazioni sui disegni di legge di riforma della legge n. 11 del 2005',in Astrid Rassegna, 2011; P. Caretti, `La legge n. 234/2012 che disciplina la partecipazione dell'Italia alla formazione e all'attuazione della normativa e delle politiche dell'Unione europea: un traguardo o ancora una tappa intermedia?', in Le Regioni, n. 5-6, 2012, p. 837 and G Rivosecchi, `La partecipazione dell'Italia alla formazione e attuazione della normativa europea: il ruolo del Parlamento', in Giornale di diritto amministrativo, n. 5, 2013, p. 463 ff.

* 344 See the Opinions dated 6 October 2009 and 14 July 2010 of the Commission for the Rules of Procedures of the Chamber of Deputies and the Letter of the Speaker of the Senate of the Republic released on 1 December 2009. C. Fasone, `Qual è la fonte più idonea a recepire le novità del Trattato di Lisbona sui Parlamenti nazionali', in Osservatorio sulle fonti, n. 3, 2010; D. Capuano, `Il Senato e l'attuazione del trattato di Lisbona, tra controllo di sussidiarietà e dialogo politico con la Commissione europea', in Amministrazione in cammino, 2011; A. Esposito, `La legge 24 dicembre 2012, n. 234, sulla partecipazione dell'Italia alla formazione e all'attuazione della normativa e delle politiche dell'UE. Parte I - Prime riflessioni sul ruolo delle Camere', in Federalismi.it, n. 2, 2013.

* 345 N. Conti and V. Memoli, Italy, in N. Conti (ed.), Party Attitudes Towards the EU in the Member States, London, Routledge, 2014.

* 346 M. Caiani and N. Conti, In the Name of the People: the Euroscepticism of the Italian Radical Right, in Perspectives on European Politics and Society, n. 15-2, 2014.

* 347 G. Nesti and S. Grimaldi, The reluctant activist: the Italian parliament and the scrutiny of EU affairs between institutional opportunities and political legacies, in The Journal of Legislative Studies, n. 24- 4,2018, p. 546 ff.

* 348 S. Cavatorto, Italy: Still Looking for a New Era in the Making of EU Policy, in C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg, J. Smith (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook, cit., p. 210 ff. M. Giuliani, Patterns of consensual law-making in the Italian parliament. In South European Society & Politics, no. 1, 2008, p. 61 ff.

* 349 E. Chiti e P. Teixeira, `The Constitutional Implications of the European Responses to the Financial and Public Debt Crises', in Common Market Law Review, n. 50, 2013, p. 683; K. Tuori, The Eurozone Crisis: A Constitutional Analysis, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014; A. Hinarejos Parga, The Euro Area Crisis in Constitutional Perspective, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015; F. Fabbrini, Economic Governance in Europe, Comparative Paradoxes, Constitutional Challenges, Oxford University Press, 2016.

* 350 J. Echebarria Fernández, `A Critical Analysis on the European Unions's Measures to Overcome the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic', in European Papers, n. 5-3, 2020, p. 1399 ff.

* 351 V. T. Raunio, `The politicization of EU affairs in the Finnish Eduskunta: Conflicting logics of appropriateness, party strategy or sheer frustration?', in Comparative European Politics, n. 14, 2016, p. 246; J. Jokela, Finland and the eurozone crisis, in P. Bäckman et al (eds), Same, same but different: The Nordic EU members during the crisis, in Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies Occasional Paper No. 1, April 2015.

* 352 For example, Prime Minister Sanna Marin delivered her statement on the MFF and the RRF in the plenary session of 9 September 2020. This communication did not result in the adoption of a resolution and was not forwarded to standing committees for further discussion.

* 353 On 27 April 2021, the Committee on the Constitution of the Eduskunta decided - by a vote of 9 to 8 - that the Own Resources Decision, the Recovery Facility and the MFF should be approved by a two-thirds majority instead of by a simple majority). A number of deputies from the majority parties who were against the stimulus package also participated in the vote.

* 354 Council Decision (EU, Euratom) 2020/2053 of 14 December 2020 on the system of own resources of the European Union and repealing Decision 2014/335/EU, Euratom.

* 355 Council Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2093 of 17 December 2020 laying down the multiannual financial framework for the years 2021 to 2027.

* 356 Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

* 357 On 10 February 2021, the Eduskunta launched the debate on the ratification of the Own Resources Decision, which generated strong criticism from the opposition. The Decision was finally approved by the Eduskunta on 18 May 2021, with a vote of 134 in favour and 57 against, and with the adoption of 8 resolutions proposed by the Finance Commission (for more details on the merit of these resolutions, see Eduskunta, Parliament has approved EU's own resources decision by a vote of 134-7, Press Release, 18 May 2021).

* 358 Since the beginning of May 2021, concerns had been raised, both at the national level and by EU leaders, about the possibility of achieving a large parliamentary majority on the RRF and the MFF due to strong opposition from minority parties and to the choice announced by the pro-European National Coalition Party (known for having MPs who were sceptical of the stimulus package) to permit its MPs to vote freely. On 12 May 2021, the President of the Eduskunta had to postpone the debate after a 14-hour oratory marathon, which ended at 4am. This decision was repeated on the morning of 14 May, after another 20-hour marathon. On both days, the debate was dominated by the Finns' Party MPs who, with the intention of delaying or preventing the vote, kept the chamber busy with speeches on the most disparate issues, including reading of extracts from the Little Red Riding Hood fairytale. On 18 May, after almost a week of postponements, the European measures were approved by a majority of 134 to 57.

* 359 During the ratification of the Own Resources Decision in the plenary session of 18 May 2021, the Finns Party tabled eight resolutions in dissent from the eight proposed by the Finance Committee; the former were rejected by the plenary. Moreover, since the beginning of the pandemic crisis, the opposition had used the instrument of dissenting opinions on several occasions during committee work (see the three dissenting opinions presented to the Declaration adopted on 8 May 2020 by the Grand Committee on EU initial financial support mechanisms, from SURE to the modification of the ESM.

* 360 T. van den Brink, `National Parliaments and the Next Generation EU Recovery Fund', in B. Dias Pinheiro and D. Fromage (eds), National and European parliamentary involvement in the EU's economic response to the COVID-19 crisis, in EU Law Live, Weekend Edition No. 36, 7 November 2020, p. 21 ff.

* 361 Based on the work conducted in the Budget Committee of the Chamber of Deputies and in the Budget and European Affairs Committees of the Senate, on 13 October 2020 the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate adopted their resolutions on the Guidelines.

* 362 On 12 January 2021, the government submitted the Draft Plan, which takes into account the views and opinions expressed by parliament on the guidelines. On 1 April, the two Houses adopted new resolutions on the Draft Plan submitted by the government.

* 363 The Italian Parliament has not formally approved the Final Plan, but on 27 April both Houses addressed, ex ante, their views and opinions to the government through the resolutions adopted on the occasion of President Draghi's communications prior to the spring meeting of the European Council.

* 364 Art. 1, par. 2 ff of the Law 29 July 2021, no. 108 attributes complete information rights and access to executive documents to the relevant standing committees in order for them to exercise their oversight function regarding the implementation of the NRRP and to prevent, detect and correct potential misalignments. Agreements between the Speakers of the two Houses of Parliaments are encouraged to promote bicameral synergies and the coordination of committee work.

* 365 Pursuant to art. 43 of the Law 23 December 2021, n. 238, fact-finding at the committee stage is expected to monitor the correct use of EU funds and the fulfilment of milestones and intermediate targets, to evaluate the economic, social and territorial impacts related to the implementation of NRRP reforms and investments.

* 366 See art. 40, para. 1, lett. a) of the Law 23 December 2021, n. 238, that modifies art. 4 of the Law on the participation of Italy in EU integration, Law 24 December 2012, n. 234.

* 367 See art. 40, para. 1, lett. b) of the Law 23 December 2021, n. 238, that modifies art. 7 of the Law n. 234/2012, specifying that the position of the Italian government at the EU level must be compliant - and not just coherent - with the acts adopted by parliament.

* 368 On the effects of the Eurozone crisis on the Italian political system, leading to a strong politicisation of European issues in electoral dynamics and fostering a transformation of party competition and the form of government under the banner of technocracy and large coalitions, see M. Comelli, `Italy's Love Affair with the EU: Between Continuity and Change', in IAI Working Paper, n. 11-8, April 2011; R. Dehousse, `Europe at the Polls: Lessons from the 2013 Italian Elections', in Policy Paper N.92, Notre Europe, May 2013; C. Froio, `The Risks of growing Populism and the European elections', in Institute of European Democracies online, n. 14, 2014. A. Capati, M. Improta, `Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde? The Approaches of the Conte Governments to the European Union', in Italian Political Science, n. 16-1, 2021, p. 1 ff.

* 369 The reference is to the 2011/2012 experience of the Monti Government - see G. Furia, `The Monti Government & the Europeanisation of Italian Politics', in O. Rozenberg (ed.), Une vie politique européenne?/A European political life?, SciencesPo - Les Dossier, May 2019 - and to the 2021 transition to the Draghi Government, see A. Dessì, `On the Brink: Mario Draghi and Italy's New Government Challenges', IAI Commentaries, 24 February 2021. On the comparison between these two experiences, see D. Garzia and J. Karremans, `Super Mario 2: comparing the technocrat-led Monti and Draghi governments in Italy', in Contemporary Italian Politics, n. 13: 1, 2021, p. 105 ff.

* 370 On the Draghi large-coalition government, which marks a reversal of direction on European issues, reaffirmed among the priorities of the Italian foreign policy, see T. Coratella and A. Varvelli, `Rome's moment: Draghi, multilateralism and Italy's new strategy', in European Council on Foreign Relations, Policy Brief, 20 May 2021.

* 371 Before the onset of the Eurozone crisis, T. Raunio and S. Hix, Backbenchers Learn to Fight Back: European Integration and Parliamentary Government, in West European Politics, n. 23-4, 2000, p. 142 ss advanced the thesis of the deparliamentarisation of the EU. After the crisis, one of the two Authors, T. Raunio, The Role of National Legislatures in EU Politics, in O. Cramme e S.B. Hobolt, Democratic Politics in a European Union Under Stress, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 1 ss. has reconsidered the thesis, arguing that the new economic governance has enabled national parliaments to exercise a tighter oversight of their executive. On this issue, see also K. Auel e O. Höing, Parliaments in the Euro Crisis: Can the Losers of Integration Still Fight Back?, in Journal of Common Market Studies, n. 52-6, 2014, p. 1184 ss. Id., National Parliaments and the Eurozone Crisis: Taking Ownership in Difficult Times?, in West European Politics, n. 38-2, 2015, p. 375 ss. D. Fromage, `The Changes provked by the European integration process - especially in times of crisis - on the relationships between Parliament and Government in France, Germany and Spain', in Revista del posgrado en derecho de la Unam, Nueva época, n. 2, 2015, p. 112 ff. A. Maatsch, Parliaments and the Economic Governance of the European Union - Talking Shops or Deliberative Bodies, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. D. Janèiæ (a cura di), National Parliaments after the Lisbon Treaty and the Euro Crisis. Resilience or Resignation?, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017. C. Fasone e N. Lupo, Constitutional Review and The Powers of National Parliaments in EU Affairs. Erosion or Protection?, ivi, p. 59 ss. B. Crum, Parliamentary accountability in multilevel governance: what role for parliaments in post-crisis EU economic governance?, in Journal of European Public Policy, n. 25, 2017, p. 268.

* 372 E. Griglio and S. Stavridis, `Inter-parliamentary cooperation as a means for reinforcing joint scrutiny in the EU: upgrading existing mechanisms and creating new ones', in Perspectives on Federalism, vol. 10, issue 3, 2018, p. I ff. On this point, see also the contribution by N. Lupo, in this Report.